by Ken Myers

[This article originally appeared in the May/June 2014 issue of Touchstone magazine.]

If asked on a game show or in some artsy version of Trivial Pursuit to connect industrialist Andrew Carnegie with music, most of us would answer “Carnegie Hall.” As it happens, New York’s famed concert venue is only one performance space made possible by Andrew Carnegie’s sense of noblesse oblige. Carnegie’s home of Pittsburgh and its suburb of Homestead, Pennsylvania also have concert halls bearing his name, as does Lewisburg, West Virginia and Dunfermline, Scotland, his birthplace.

Dumfermline is also the home of the Carnegie UK Trust, one of the many charitable organizations enabled by Carnegie’s largess. Established in 1913 to improve “the well-being of the masses of the people of Great Britain and Ireland,” the Trust is another important link between the steel and railroad billionaire and music, a link of particular interest to Christians who care about stewarding the great legacy of sacred choral music.

In the 1920s, the Trust supported a massive project of scholarship and publishing that transformed the musical life of the U.K. and of many individuals and communities far abroad. That project was the publication of a ten-volume collected edition of music by the great Tudor-era composers. Between 1922 and 1929, Oxford University Press released the complete edition of Tudor Church Music, and also made available performing editions of the music for purchase by choirs. Most of this music had until then been unavailable in modern editions, which meant that, unless one had access to scores hand-copied from manuscripts preserved in libraries, singing or hearing this music was impossible.

Especially for English-speaking Christians, this was a huge loss. The music in question was by some of Britain’s greatest composers, working in a period widely acknowledged as the high watermark of choral music. These are the Shakespeares and Donnes of English music, and many of their compositions were settings of sacred texts for use in liturgy or in private devotional settings. (This was, after all, a time when most educated people could read music, and it was not uncommon to sit at table after dinner and distribute part-books for four- and five-part singing, often of sacred texts.)

Thanks to Andrew Carnegie’s generosity, this forgotten music was recovered and made widely available for churches and college choirs. Today, nearly a century after Carnegie’s death, this music is still part of the standard repertoire for many churches.

The gems from Stile Antico

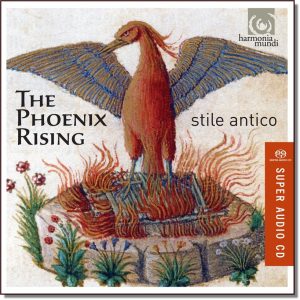

The Phoenix Rising is the title of a 2013 CD that features some of the most notable gems revived in Tudor Church Music. The disc is the eighth release by the young choral ensemble Stile Antico; all of their recordings have featured sacred choral music from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, much of it by English composers and all of it richly rewarding.

This repertoire is often dubbed “early music,” a distant and exotic phenomenon, of interest only to very specialized ears. I like to think of it as music from before the Enlightenment, music from an era in which the Christian account of nature and supernature was quietly assumed rather than nervously defended. It was a time when imaginations were attuned to notions of cosmic order, not defiantly assertive in the face of cosmic chaos. As a twenty-first century Christian, I am more confident that this is “our music” than I am about the “late music” (some of it too late) of our own era.

Music by William Byrd (1543-1623) comprises about 30 minutes of this disc, featuring his Mass for Five Voices and his setting of the Eucharistic hymn Ave verum corpus. This latter work is probably the best-known piece on the recording. The text, from the fourteenth century, begins (in translation): “Hail, true Body, born of the Virgin Mary, who having truly suffered, was sacrificed on the cross for mankind, whose pierced side flowed with water and blood. . . . ”

Music by William Byrd (1543-1623) comprises about 30 minutes of this disc, featuring his Mass for Five Voices and his setting of the Eucharistic hymn Ave verum corpus. This latter work is probably the best-known piece on the recording. The text, from the fourteenth century, begins (in translation): “Hail, true Body, born of the Virgin Mary, who having truly suffered, was sacrificed on the cross for mankind, whose pierced side flowed with water and blood. . . . ”

Byrd’s setting is austere and reverent. At the phrase, “was sacrificed on the cross for mankind,” he uses harmonic tension to underscore the pain Christ endured. The four vocal lines separate and flow downward in separate streams of melody on the line “flowed with water and blood.” Later in the piece, on the words “have mercy on me,” he employs a so-called harmonic “false relation” to ignite a moment of dissonance and emotional intensity. This four-minute musical prayer brings to mind Josef Pieper’s observation that “music is alone in creating a particular kind of silence, though by no means soundlessly.”

Two works by Byrd’s teacher and colleague Thomas Tallis (c.1505-1585) are also featured on The Phoenix Rising. One of these, In ieiunio et fletu (“In fasting and weeping,” from Joel 2:17) displays remarkably surprising harmonic transitions that convey the drama of the priests of Israel crying out to Yahweh: “Spare thy people.”

Space prevents me from introducing the pieces by Orlando Gibbons, Thomas Morley, Robert White, and John Taverner also beautifully sung by Stile Antico on this instructively programed and elegantly packaged disc (all of their previous recordings are similarly thoughtful and compelling). Taken together, this anthology of ten glorious works is a splendid introduction to the legacy of sacred choral music from a tempestuous time in English political and religious life, a time nonetheless rich in the cultivation of the art of prayerful song.

Listen to Stile Antico sing Byrd’s Ave verum corpus