In 2008, the Church Music Association of America published A Byrd Celebration, compiling lectures given over the years at the annual William Byrd Celebration in Portland, Oregon. One of the lecturers was Duke University musicologist Kerry McCarthy, author of Liturgy and Contemplation in Byrd’s Gradualia (Routledge, 2007). In a brief biographical sketch in A Byrd Celebration, McCarthy wrote:

William Byrd was the most famous and best-loved of early English composers. His entire life was marked by contradictions; as a true Renaissance man, he did not fit easily into other people’s categories. He was renowned for his light-hearted madrigals and dances, but he also published a vast, rather archaic cycle of Latin music for all the major feasts of the church calendar. He lived well into the seventeenth century without writing songs in the new Baroque fashion, but his keyboard works marked the beginning of the Baroque organ and harpsichord style. Although he was a celebrated Anglican court composer for much of his life, he spent his last years composing for the Roman liturgy, and died in relative obscurity. In the anti-Catholic frenzy following the 1605 Gunpowder Plot, some of his music was banned in England under penalty of imprisonment; some of it has been sung in English cathedrals, more or less without interruption, for the past four centuries.”

As members of a parish in Virginia, the name “Byrd” has special resonance. In 1677, the prominent English-born colonial land-owner, fur trader, and member of one of the First Families of Virginia, William Byrd I (1652–1704), was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. His son, William Byrd II (1674–1744), is considered the founder of the city of Richmond. William Byrd III (1728–1777) inherited 179,000 acres of Virginia land, all of which he eventually sold to pay off gambling debts (he is also said to have organized the first major horse race in the New World). In the twentieth century, there were the two Harry Byrds, responsible for the Shenandoah National Park and the powerful political machine known as the Byrd Organization.

William Byrd the composer may have been a distant kin of these Virginians, but biographers know nothing about his parentage, or even about his birthplace. We can place him in London some time in his late teens, since we know he studied with Thomas Tallis (then at the Chapel Royal) before accepting a position as Organist and Master of the Choristers at Lincoln Cathedral in early 1563. By then he had already begun composing vocal and keyboard works.

Byrd remained in Lincoln until 1570, by which time he had become quite accomplished in composition, especially for the favored English keyboard instrument, the virginal. Joseph Kerman has commented; “A striking feature of this early music is the great number of styles, forms and genres that Byrd essayed and the rapid, sure moulding of them all into something individual.”

In 1572, he was appointed as one of the Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal, the prestigious royal choir that dates to the eleventh century. By that time, he had composed most of the English-language liturgical music he would write, the quality of which surely helped him land the position at court, where he joined his former teacher, Thomas Tallis.

Fortunately for Byrd, Queen Elizabeth — in spite of her championing of the Protestant cause — was fond of the use Latin texts in liturgical music. Byrd never abandoned his Roman Catholic convictions, and some of his most powerful music expresses the sense of tension felt by English Catholics in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Byrd and his family were frequently fined for refusing to become Protestant, but his powerful friends in the nobility — not to mention the fondness the Queen had for his music — kept him out of prison.

Beginning in the 1580s, while still composing anthems and service music in English for “official” use, Byrd increased his output of Latin motets (he eventually wrote about 150), some of which were intended to be sung in secret (because illegal) Roman Catholic services held in private chapels on estates owned by some of his patrons. In 1593, he moved away from London to a property in Essex, the site of a significant Catholic community, for whose masses Byrd contributed some remarkable compositions (some of which our choir has sung).

Joseph Kerman writes:

After 1590 Byrd’s attitude towards Latin sacred music underwent a significant change. The early motets were monumental and expressive; they were also personal in the sense that the texts represented the free choice of Byrd and his patrons — penitential meditations or outbursts in the first person singular as well as prayers, exhortation and protests on behalf of the Catholic community. He now started work on a grandiose scheme to provide music specifically for Catholic services.

Between 1592 and 1595, the three mass settings Byrd composed were quietly published, in slim books with no title pages. But by 1605, Byrd began to be braver and published more openly the first of three collections of music intended for the Catholic liturgy. These Gradualia were settings for the Propers of the Mass, many of which are used in our Anglo-Catholic liturgy. (Byrd shrewdly obtained permission from the Bishop of London, Richard Bancroft, before these works were published.)

In the Latin dedication to his patron in Book I of his Gradualia, Byrd wrote:

For even as among artisans it is shameful in a craftsman to make a rude piece of work from some precious material, so indeed to sacred words in which the praises of God and the Heavenly host are sung, none but some celestial harmony (so far as our powers avail) will be proper. Moreover in these words, as I have learned by trial, there is such a profound and hidden power that to one thinking upon things divine and diligently and earnestly pondering them, all the fittest melodies occur as if of themselves and freely offer themselves to the mind which is not indolent or inert.

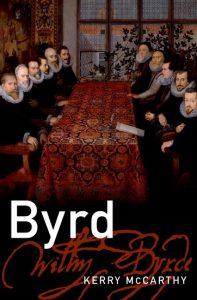

In 2013, Kerry McCarthy (quoted above) wrote a biography called simply Byrd (Oxford University Press). Here is an excerpt from the interview I did with her about that book (originally featured on volume 125 of the MARS HILL AUDIO Journal). In the interview, she talks about compositions by Byrd that our choir has sung, including his Mass for three voices. She says something about this work that members of our choir have also said: that every time you sing it, you discover something new. That is a mark of Byrd’s insight as a composer.

This BBC documentary, Playing Elizabeth’s Tune: Catholic Composer and Protestant Queen, explains in greater detail the delicate negotiating Byrd managed to achieve to keep out of trouble as a Roman Catholic in a country in which such commitments were often regarded as implicitly treasonous. Hosted by conductor Charles Hazlewood, the film includes performances of some of Byrd’s richest Latin works by The Tallis Scholars, conducted by Peter Philips.

MORE TO READ:

A short biography of William Byrd

by Jeremy Summerly is at the

website of the BBC Music Magazine

Works by William Byrd in the

All Saints Choir repertoire

Agnus Dei (from Mass for three voices)

Alleluia! Cognoverunt discipuli

Bow thine ear, O Lord

Cibavit eos

Haec dies

Justorum animae

Lord, hear my prayer

Miserere mei, Deus

Oculi omnium

Prevent us, O Lord

Rorate Coeli

Sacerdotes Domini

Sanctus and Benedictus (from Mass for Three Voices)

Sanctus and Benedictus (from Mass for Four Voices)

Visita quaesumus, Domine