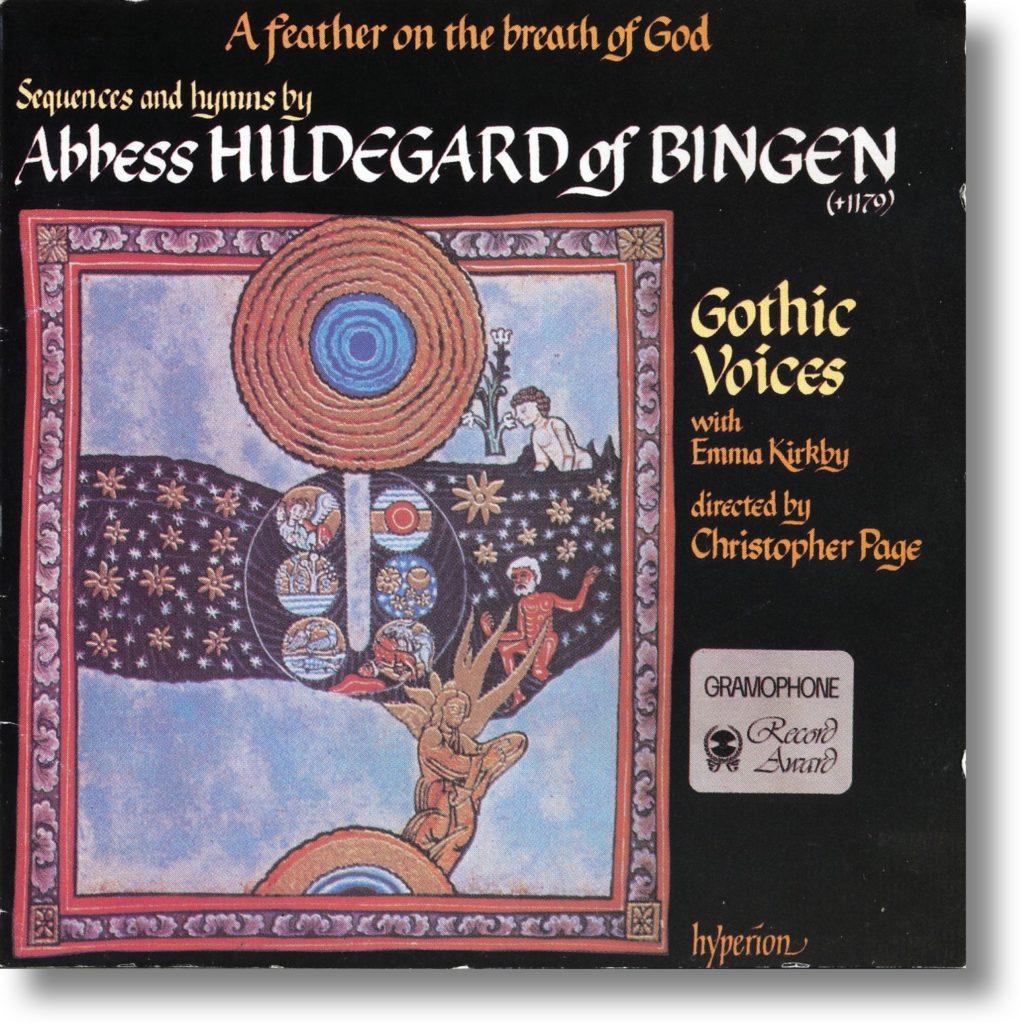

Christopher Page is Professor of Medieval Music and Literature, a Fellow of the British Academy, and a Fellow at Sidney Sussex College, University of Cambridge. He was the founding director (in 1980) of the British ensemble Gothic Voices. That group’s first CD, A Feather on the Breath of God, featured sacred vocal music written in the 12th century by the German abbess Hildegard of Bingen. That recording did a great deal to alert many music lovers to Hildegarde’s compositions, and to the voice of one of the singers in the ensemble, a then-little-known soprano with a pure, clear voice named Emma Kirkby.

In 2015-2016, Page gave a series of lectures about Medieval music for Gresham College, which was founded in 1597 and has been providing free lectures within the City of London for over 400 years. The series was titled “Music, Imagination, and Experience in the Medieval World.” Recordings of the six lectures are presented below.

Another series of lectures by Page — “The Christian Singer from the Gospels to the Gothic Cathedrals” — is available here. And an interview with Page about his book The Christian West and Its Singers: The First Thousand Years (Yale University Press, 2010) may be heard here.

Lecture 1: The Stations of the Breath

At the heart of virtually all the medieval music that survives, is the human voice. This is an ancient heritage. The early Christians under the Roman Empire believed themselves to be engaged in a pilgrimage through a transitory world, where they were strangers, to their true home and an eternal liturgy “where my servants shall sing for joy of heart,” as St John the Divine says in Revelation. But why have singing in worship? What was to be gained, in the early Church and in its medieval descendant, by having a choir singing snippets of the Scripture, often extracted from their original context and sewn together in new patterns? We shall find that the answer lies in the breathing body.

Lecture 1: The Stations of the Breath

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 2: Chant as Cure and Miracle

As the monks were singing in a French abbey of the twelfth century, a cripple, who had crawled into the church suddenly, began to cry aloud and to extend his contorted limbs, “and thus he that came into the church on four legs departed on two.” It has been generally forgotten that men and women in the Middle Ages believed that the singing of monks and clergy during worship had the ability to produce sudden and dramatic cures: the music entered the ear as a healing spiritual balm that could hasten results beyond the reach of any contemporary physician.

Crooked limbs became straight with a loud, cracking sound; wounds and sores were closed and healed. This lecture is devoted to this little-known landscape of medieval musical experience.

Lecture 2: Chant as Cure and Miracle

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 3: To Sing and Dance

During the eighteenth century, Western Europe gradually relinquished a form of musical experience that had been vital to the life of royal courts, town squares and streets for the best part of a thousand years: the company dance performed by dancers, especially young women, holding hands and moving in a ring or a line. Medieval poems, sermons, chronicles and a great many other kinds of writing reveal much about these dances: where they were performed, when, by whom and to what effect, enabling us to restore a picture that has greatly faded over the centuries.

Lecture 3: To Sing and Dance

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 4: To Chant in a Vale of Tears

According to one early-medieval author, “there are many who are moved by the sweetness of singing to bewail their sins, and who are readily brought to tears by the sweet sounds of a singer.” A thousand years later, Hector Berlioz tells how a musician was so moved during the performance of an opera that “two streams of tears burst violently from his eyes, and he wept so hard that I was compelled to lead him out of the hall.” Tears and music have a long history together, but a show of tears means different things at different times. The purpose of this lecture is to explore the nature of a lachrymose response in the medieval experience of music.

Lecture 4: To Chant in a Vale of Tears

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 5: The Mystery of Women

During the last thirty years, the name of Hildegard of Bingen (d. 1179) composer, abbess and naturalist, has been gradually rescued from obscurity, notably by recordings of her works. The lecture will provide an opportunity to hear some of Hildegard’s most impressive compositions but also to explore more widely the phenomenon of the medieval female composer. For while Hildegard was unique, she was not alone; the richness of the musical remains she has left eclipse every competitor, and yet there were many other female mystics who created rhapsodic spiritual song whose works have not survived. Many of them are little known, but here they will step into the light.

Lecture 5: The Mystery of Women

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 6: The Lands of the Bell Tower

Many thousands of visitors to London each year return home thinking that Big Ben is the name of the great clock tower at Westminster. Londoners know that this is the name of the bell. This is a legacy from the Middle Ages when bells had names, “tongues” and “mouths.” They could be baptized and might even be taken down, and filled with thorns, as a punishment if they did not ring of their own accord in a time of crisis. Where the bell-towers on the skyline ended, there Christian Europe had its frontiers.

This final lecture of the series, given in the church whose bells are commemorated in nursery rhyme as the “bells of the Old Bailey,” will explore the place of the bell tower and its inhabitants in the medieval imagination.

Lecture 6: The Lands of the Bell Tower

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.