In a tiny essay called “Music and Silence,” the Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper observes:

“Music and silence: these are two things which, according to C. S. Lewis, cannot be found in hell. We ought to be somewhat surprised when we first read the phrase: music and silence — what a strange pairing! But then the heart of the matter becomes more and more clear. Obviously, what is here meant by silence, stillness, hush, is something quite different from that malignant absence of words which already in our present common existence is a parcel of damnation. And, as far as music is concerned, it is not difficult to imagine that in the Inferno its place is taken by noise, ‘infernal noise’, pandemonium. But then, almost imperceptibly, another aspect of the issue emerges, namely, that music and silence are in fact ordered toward one another in a unique way. Both noise and total silence destroy all possibility of mutual understanding, because they destroy both speaking and hearing. . . . [T]o the extent that it is more than mere entertainment of intoxicating rhythmic noise, music is alone in creating a particular kind of silence, though by no means soundlessly. . . . It makes a listening silence possible, but a silence that listens to more than simply sound and melody. . . . Far beyond this, music opens up a great, perfectly dimensioned space of silence within which, when things come about happily, a reality can dawn which ranks higher than music.”

More recently, in a book about the contemporary composer Arvo Pärt, conductor Paul Hillier has written:

“All music emerges from silence, to which sooner or later it must return. At its simplest we may conceive of music as the relationship between sounds and the silence that surrounds them. Yet silence is an imaginary state in which all sounds are absent, akin perhaps to the infinity of time and space that surrounds us. We cannot ever hear utter silence, nor can we fully imagine such concepts as infinity and eternity. When we create music, we express life. But the source of music is silence, which is the ground of our musical being, the fundamental note of life. How we live depends on our relationship with death; how we make music depends on our relationship with silence.”

On Trinity Sunday (June 4), our choir will sing The Deer’s Cry, a 2007 composition by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. This work is based on a prayer attributed to St. Patrick.

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me,

Christ in me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ on my right, Christ on my left,

Christ when I lie down, Christ when I sit down,

Christ in me, Christ when I arise,

Christ in the heart of everyone who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me,

Christ in every ear that hears me.

Christ with me.

The text will be familiar to many in the parish, since we sing these words (with slight variations) every time we sing the hymn “I bind unto myself today.” You can learn more about the history of this remarkable prayer on this page.

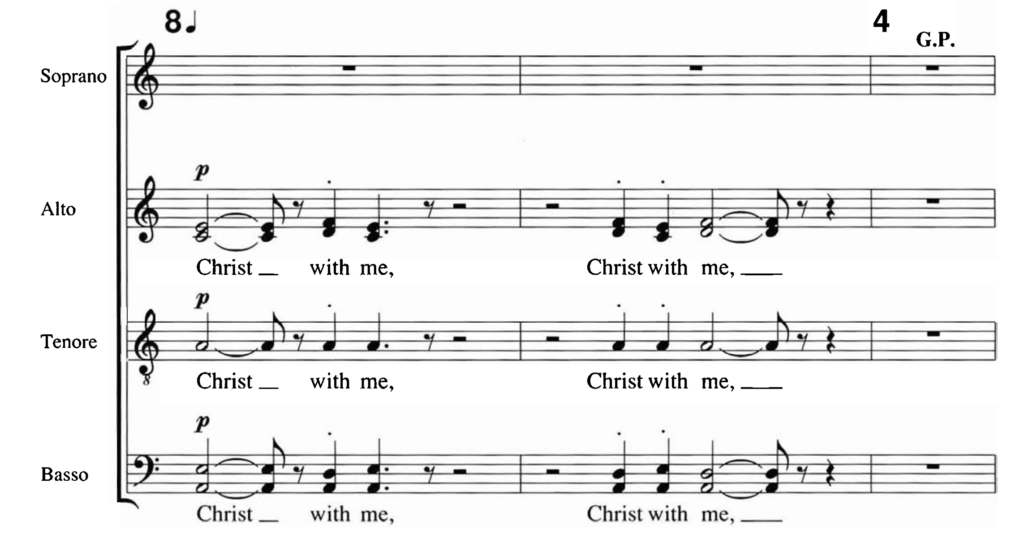

Arvo Pärt’s setting of this text sustains its essential prayerful posture by a dramatic use of silence. Here is the first line of the score:

In case you can’t read music, those small horizontal bars that appear between the groups of notes are rests, indicating that for a certain number of beats, the singers remain silent. And few pieces of music entwine silence within the musical tapestry as much as does The Deer’s Cry.

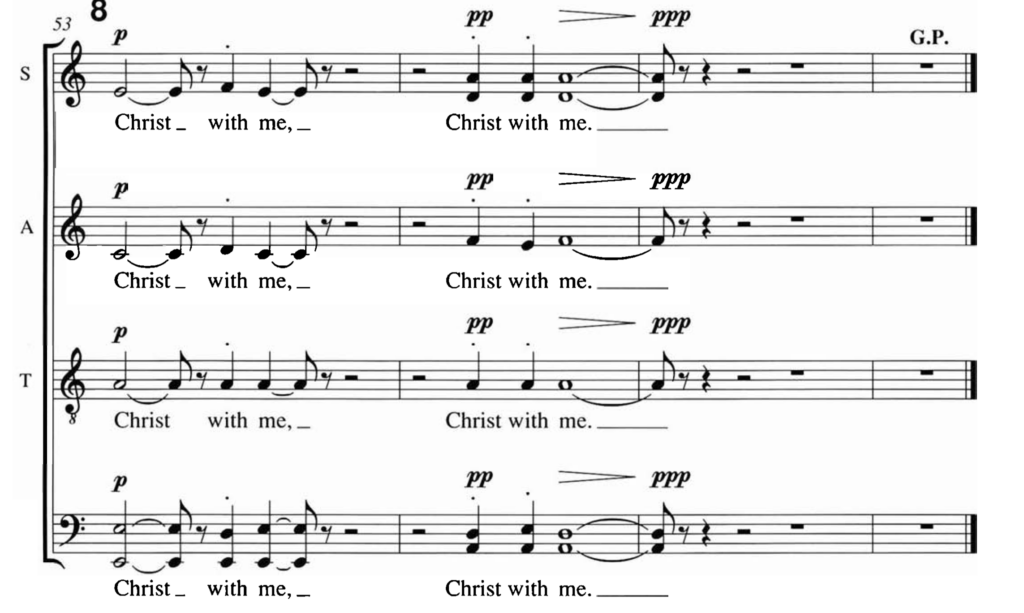

Here is the last line of the score:

Even though the choir’s singing has ended with the last note, on the word “me,” the music continues in silence for many beats. Remember Josef Pieper’s insight that “music opens up a great, perfectly dimensioned space of silence within which, when things come about happily, a reality can dawn which ranks higher than music.” That seems to be Arvo Pärt’s intention in including all of those rests at the end of the score. Our choir members hope we can convey something of that higher reality when we sing this at Holy Communion.

On this page, you can read about how Arvo Pärt’s approach to musical composition has evolved over the years, an evolution that resisted many fashionable musical practices in the twentieth century. At the bottom of the page, you can listen to an interview with conductor Peter Phillips about the music of Arvo Pärt.

Theologian Peter Bouteneff has written a thoughtful companion and guide to Arvo Pärt’s music called Arvo Pärt: Out of Silence. Dr. Bouteneff is founding director of the Arvo Pärt Project at St. Vladimir’s Seminary.

Below, you can hear an interview with Dr. Bouteneff about Pärt’s beliefs and his works.