by Ken Myers

[This article originally appeared in the November/December 2016 issue of Touchstone magazine.]

When I was in high school, a remarkable music teacher introduced me to some recordings of Christmas music by a group called the Elizabethan Singers, led by Louis Halsey. The records featured mid-twentieth-century arrangements of traditional carols, some of which were familiar (“Away in a Manger,” to the tune CRADLE SONG, in a delicate setting by Hugo Cole, or “Good King Wenceslas,” arranged by Malcolm Williamson, or “The Holly and the Ivy,” set by Benjamin Britten). But many of the arrangements were of texts and tunes I had never heard, but which have since become as familiar as “Silent Night,” and much more treasured as they are less susceptible to treacly renditions.

I later sang from the scores to these works, which contain footnotes with wise counsel for conductors and performers. In singing Cole’s “Away in a Manger,” for example, we are warned: “Avoid needless sentimentality; the tune has its own charm,” while Edmund Rubbra’s version of the traditional Polish carol “Infant Holy” includes the rubric “The dignity and beauty is lost if sung too quickly.”

Musical Re-enactment

I heard and began singing these mid-century arrangements in the late 1960s, which made them contemporary Christian music. But what captivated me was not the contemporaneousness but the capacity of the music to be both emotionally engaging and intellectually compelling, and thus a more suitable and versatile vessel for expressing the realities revealed in the Nativity of our Lord. The musical vocabulary of these carols have an organic connection with much earlier music; the musical imagination of composers such as Rubbra and Britten (and their much younger successors) was, after all, shaped by a centuries-long tradition of sacred choral composition.

Within that tradition is a commitment to make the singing and hearing of music within the liturgy into a musical re-enactment — not just a narration or description — of the mysteries beneath the events of God’s engagement with Man. None of those mysteries is more central than the Incarnation, which is one reason why some of the most imaginative music in the tradition is associated with Christmas.

In the historic liturgy of the Church, the Antiphon to the Magnificat appointed to be sung on the vespers on Christmas Day is “Hodie Christus natus est.” “Today Christ is born. Today the Savior appeared. Today on Earth the angels sing, archangels rejoice. Today the righteous rejoice, saying: Glory to God in the highest. Alleluia.” Not surprisingly, there are hundreds of settings of this text, but the ones that display the theme of glory most fully are those inspired by the Venetian polychoral style of the late Renaissance and early Baroque period. In this style, choirs bounce musical phrases back and forth, reinforced in producing their glorious sound by robust brass choirs. It is a fitting form for singing lots of “Gloria” and “Alleluias,” for sonically enacting glory and not just singing about it.

Giovanni Gabrieli’s two settings of the “Hodie,” one for two four-part choirs, one for two five-part choirs — are among the most famous. Heinrich Schütz — a German trained by Gabrielli — also composed a “Hodie” that would have made his Venetian teachers proud. Other Renaissance masters who set this text include Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and Jan Sweelinck.

Two Metaphysical Mysteries

In addition to the theme of glory represented in Christmas music (including many hymns and carols), there are also the more metaphysical mysteries of the Virgin Birth and the Incarnation, both of which have been subjects treated by composers to great effect. Two examples will have to suffice in this short space.

First, the text “Praeter rerum seriem” (“This is no normal scheme of things”), set most famously by Josquin des Prez (c. 1450-1521). This seven-minute motet begins with the declaration: “This is no normal scheme of things: God and man is born of a virgin mother.” The final lines of the text address the Virgin Mary: “The beginning and end of your giving birth who can really know? By God’s grace, which orders all things so smoothly, your childbearing confronts us with a mystery. Hail, Mother.”

Josquin’s setting is for seven vocal parts, three high, three low, and one in the middle. The dramatic texture of the work relies on contrasts and interactions between the upper and lower voices. The first several lines of the music — the initial announcement of the uniqueness and strangeness of this birth — are sung by two low bass lines, sounding as if they are emerging from the depths of the earth. (A conductor friend said that when he rehearsed this with his choir, he told them it should sound “spooky.”) I wonder whether Josquin had Psalm 139 in mind, the passage in which the Psalmist says that his being was woven by God “in the depths of the earth.” Joaquin achieves a remarkable sense of supernatural (and subterranean) power with this opening effect.

The text for “Mirabile mysterium” (“Wondrous mystery”)— the Antiphon to the Benedictus at Lauds on the Feast of Circumcision — is another opportunity for composers to consider how to depict marvelous abnormality: “A wondrous mystery is declared today, an innovation is made upon nature; God is made man; that which he was, he remains, and that which he was not, he takes on, suffering neither commixture nor division.”

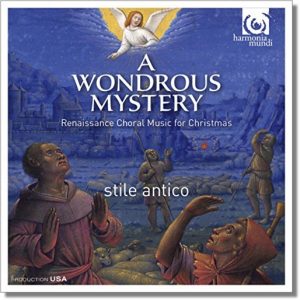

A snappy lyric it’s not. But in the hands of Jacob Handl (1550-1591), it is an occasion to demonstrate how music can provide an experiential knowledge of realities too deep for words. In his setting of “Mirabile mysterium,” Handl uses unpredictable harmonic progressions to capture the sense that something disorienting — or, better, re-orienting — is happening in the Incarnation, and thus, in the world. At the end of the work, the Latin phrase “non commixtionem passus” (“suffering no commixture”) is repeated over and over, underscoring this important Christological definition. Handl’s setting is one of many remarkable Christmas works featured on A Wondrous Mystery, a recording released last year by the ensemble Stile Antico. If you crave release from needless sentimentality this Christmas, this is a good place to start

A snappy lyric it’s not. But in the hands of Jacob Handl (1550-1591), it is an occasion to demonstrate how music can provide an experiential knowledge of realities too deep for words. In his setting of “Mirabile mysterium,” Handl uses unpredictable harmonic progressions to capture the sense that something disorienting — or, better, re-orienting — is happening in the Incarnation, and thus, in the world. At the end of the work, the Latin phrase “non commixtionem passus” (“suffering no commixture”) is repeated over and over, underscoring this important Christological definition. Handl’s setting is one of many remarkable Christmas works featured on A Wondrous Mystery, a recording released last year by the ensemble Stile Antico. If you crave release from needless sentimentality this Christmas, this is a good place to start

Jan Sweelinck’s Hodie Christus natus est

performed by the Cambridge Singers, directed by John Rutter

Josquin des Prez’s Praeter rerum seriem

performed by Alamire, directed by David Skinner

Jacob Handl’s Mirabile mysterium

performed by Stile Antico