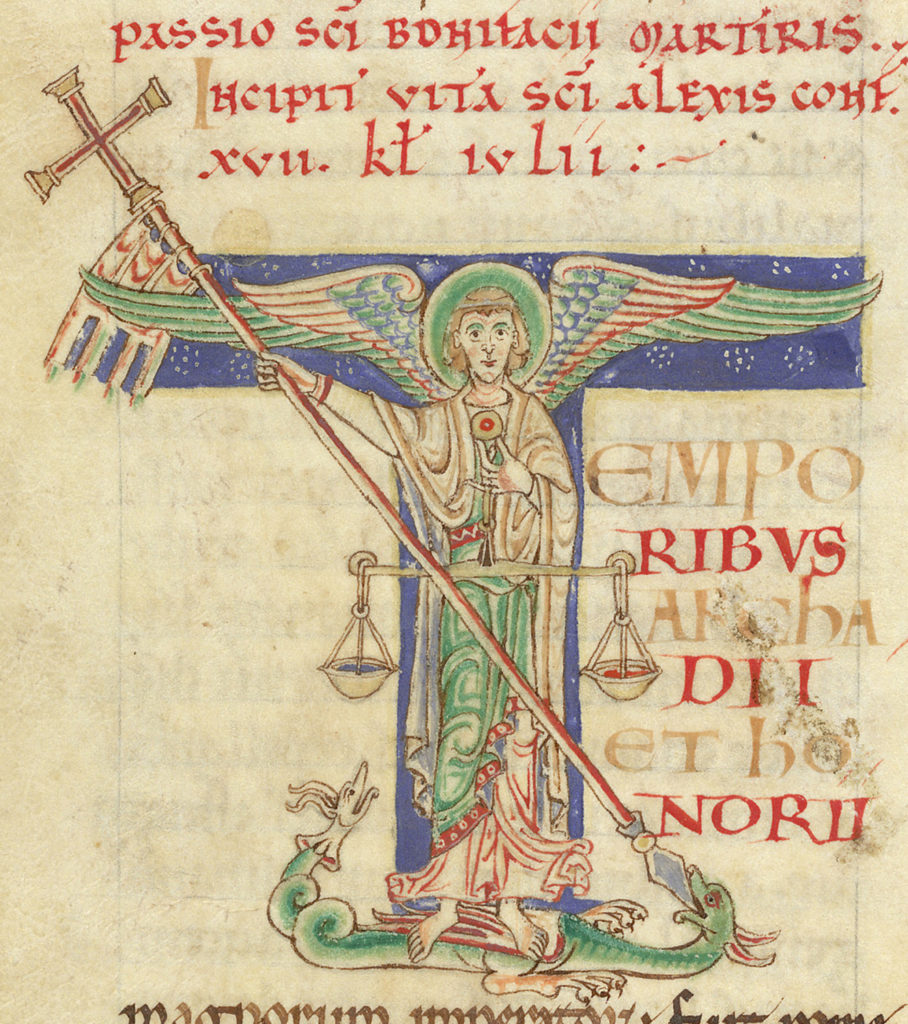

The Feast of St Michael and All Angels (observed on September 29th and also known as Michaelmas) is an occasion for the celebration of victory over the powers of Satan. As musicologist Julian Mincham writes in a commentary on this cantata, St. Michael, who was sometimes portrayed as the dragon slayer, “was the leader of God’s army of angels, a figure who inspired fortitude and ensured the soul’s safe passage to the Throne of God. He thus symbolizes the victory of righteousness triumphing over evil.”

Conductor John Eliot Gardiner suggests that Johann Sebastian Bach’s imagination was primed for decades to bring his most elaborate skills to bear when conveying the meaning and character of the angelic hosts. “The concept of a heavenly choir of angels was implanted in Bach as a schoolboy in Eisenach, when even the hymn books and psalters of the day gave graphic emblematic portrayal of this idea; the role of angels, he was instructed, was to praise God in song and dance, to act as messengers to human beings, to come to their aid, and to fight on God’s side in the cosmic battle against evil.”

The cantata Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir (“Lord God, we all praise you”), was composed for use in the liturgy on this feast day and first performed in 1724. It is one of Bach’s larger scale cantatas; though of average length, the number of musicians it requires is relatively grand. In addition to a full choir and four soloists, it features three trumpets and timpani (giving a martial and/or royal feel to the music), three oboes, a flute, strings, and continuo (which sometimes means a bassoonist sitting with oboes). This complement of instruments is, as Mincham points out, “reminiscent of the opening chorus of the Christmas Oratorio or the “Cum Sancto Spiritu” from the B-minor Mass. This is an uplifting of voice and soul to praise the Lord and His angels.” (The video commentary near the bottom of this post offers more details on how these instruments are arranged in three groups of three, which adds a Trinitarian flavor to the ensemble.)

The angels are being honored in this opening chorus, but it is the Lord who is being being praised, specifically for having created the angels, as the text of the magnificent opening chorus makes clear:

Lord God, we all praise you

and we shall rightly give you thanks

now for your creation of the angels

who hover around you, about your throne.

This text is from a hymn that was central to the celebration of Michaelmas among Lutherans in Bach’s day. It is from a hymn adapted by Wittenberg scholar Paul Eber (1511-1569) of Latin verses by Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560), a close associate of Martin Luther.

The melody traditionally linked with this hymn and brilliantly elaborated in this opening chorus is known to many contemporary Christians as OLD HUNDREDTH. It is the tune to which countless congregations sing the words “All people that on earth do dwell” or “Praise God, all creatures here below.” Written by the Genevan composer Louis Bourgeois (c.1510-c.1560), the tune first appeared in the Genevan Psalter in 1551, and soon became a common feature in Protestant worship in many churches. Among Lutherans in Bach’s day, it was the tune sung to Paul Eber’s hymn every Michaelmas. So Bach’s use of it in this opening chorus (and, with some rhythmic changes, in the final chorale of the work) would have had his Leipzig congregation humming along happily.

Conductor Masaaki Suzuki explains what’s going on with the instruments that are playing while the choir is energetically singing its praises:

The sound image gains breadth from the contrast between three separate instrumental groups, in the antiphonal tradition of the seventeenth century: strings, a trio of oboes and an ensemble of trumpets and timpani, each with its own thematic material. The strings are characterized by bustling semiquavers [i.e., sixteenth notes]— perhaps an illustration of the angels around the throne; the oboes play one degree more slowly, in quavers [i.e., eighth notes], and often contribute echo motifs to the other two sound groups; and the trumpets and timpani — symbols of dominance in Bach’s time and thus essential in a piece honouring the heavenly ruler — crown the sound image with signal-like triad figures supported by drumbeats.

Here is the opening chorus sung by the Holland Boys Choir and the Netherlands Bach Collegium, conducted by Pieter Jan Leusink.

This chorus is followed by a brief alto recitative. Mincham reminds us that Luther’s angels — and hence Bach’s — “were not passive creatures. . . . His angels were an army in readiness to take the fight for goodness and redemption directly to Satan himself.” The angels are described in this recitative not just as heroes, but as weapons!

Their dazzling brilliance and lofty wisdom show

how God bends down to us men,

since he has created such heroes,

such weapons for us.

They do not rest from honouring him

all their diligence is directed to this purpose,

that they, Lord Christ, are around you

and are around your poor little flock:

how necessary is this vigilance of theirs

against the rage and might of Satan?

Here is the alto recitative sung by soloist Richard Wyn Roberts, with the English Baroque Soloists conducted by John Eliot Gardiner.

Next is a bass aria, in which the principal figure is the dragon whose defeat at the hands of St. Michael and his fellows is recounted in the Epistle reading for Michaelmas, Revelation 12:7-12.

The old dragon burns with envy

and constantly plots new suffering

so that he may divide the little flock.

He would willingly wipe out what is God’s,

soon he uses his cunning

since he knows neither peace nor rest.

If the opening chorus presented Bach’s congregation with a familiar hymn tune, Masaaki Suzuki describes the bass aria as a “display piece the like of which Bach’s Leipzig congregation would most certainly never have heard. The trumpets play as if in combat with the ‘old dragon.’” To underscore the fact that a battle — in sound — is being waged, the melody of the first line in this aria copies a then well-known military signal.

Here is the aria sung by bass Klaus Mertens, along with the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir, conducted by Ton Koopman.

This combative aria is followed by a comforting recitative, a duet featuring soprano and tenor soloists. The text brings in the Old Testament story of angelic protection of Daniel in the fiery furnace to underscore the power of God’s army.

But how fortunate we are that day and night

the host of angels keeps watch

to destroy Satan’s onslaught!

A Daniel, who sits among lions

finds out how the angel’s hand protects him.

When the heat there

in the furnace of Babel does no harm

those who believe let a song of thanks be heard,

so it happens now in danger

the angels help still appears.

Here is the duet sung by soprano Malin Hartelius and tenor James Gilchrist, with the English Baroque Soloists, conducted by John Eliot Gardiner.

There follows a prayer to God, the “Prince of cherubim,” for continued protection by heavenly powers.

Grant, O Prince of cherubim

that this exalted host of heroes

may always serve those who believe in you,

that on Elijah’s chariot

they may carry them to you in heaven.

This is sung by a tenor soloist, paired with a virtuoso flute, perhaps calling to mind how swiftly Elijah’s chariot can travel. The aria is sung here by tenor Paul Agnew, with the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir, conducted by Ton Koopman. (Sorry, but I don’t know who the flute player is!)

The final chorale continues in a mode of prayer, presenting two more verses from Paul Eber’s Michaelmas hymn, sung to OLD HUNDREDTH in an elegant triple meter,

Therefore we rightly praise you

and thank you, God, for ever

just as the dear host of angels also

praises you now and forever.

And we pray that you may be willing at all times

to order them to be prepared

to protect this little flock of yours

so that it holds in reverence your divine word.

The performance of this chorale presented below features the choral ensemble Vox Nidrosiensis, and the instrumental ensemble Trondhein Barokk (both groups from Norway), conducted by Sigiswald Kuijken.

The Netherlands Bach Society has recorded Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir (BWV 130) in a live performance, which is accompanied on their All of Bach website with this informative video featuring conductor Jos van Veldhoven.

Here is the complete (and stirring!) performance of Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir by the Netherlands Bach Society.