During Communion in our parish, we often sing the text to St. Thomas Aquinas’s great Eucharistic hymn, which begins “Now my tongue the mystery telling” (Hymn #199). The tune to which we usually sing this hymn is PANGE LINGUA, a plainchant melody that comes from the Sarum Use.

We also sing that tune on Good Friday, with the text of a different hymn, this one about the Cross and the Crucifixion, a hymn which begins: “Sing, my tongue, the glorious battle.”

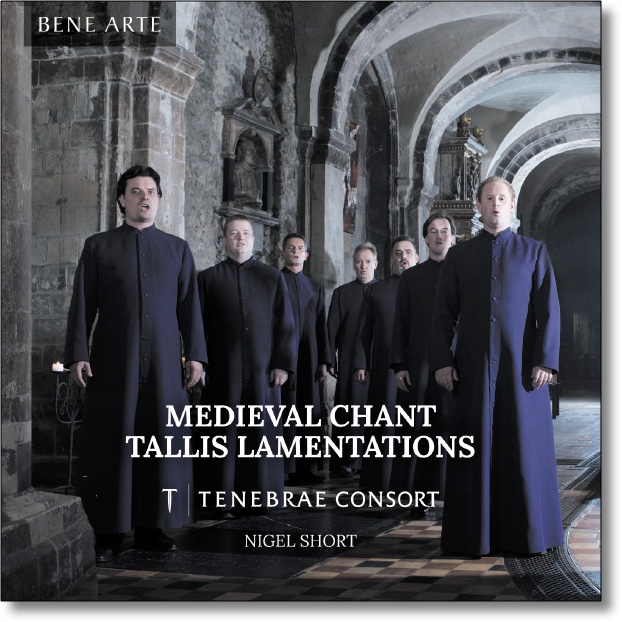

Here is that Holy Week hymn sung in its original Latin form by the Tenebrae Consort, directed by Nigel Short.

This is from a recording that presents a collection of music for Passiontide. The bulk of the album comprises the plainchant antiphons, hymns, psalms, and canticles sung at Compline (i.e, evening prayers) during Passiontide in the Sarum Use, the liturgical order developed over centuries in the worship at Salisbury Cathedral.

As John Rowlands-Prichard explains in the album’s notes, “Salisbury was renowned across Europe as a centre of ritual excellence, both in various embellishments to the basic Roman liturgy, and in the care of its observation and performance.”

The English composers who contributed to that excellence include John Sheppard, whose setting of Media vita was explored earlier this week (and whose In Manus Tuas is on this album), and Thomas Tallis (1505-1585), whose settings of the Lamentations of Jeremiah are the polyphonic centerpiece in this collection of Passiontide music.

The Old Testament book we know as Lamentations originally bore no title. The ancient texts of this book bore a superscription: the opening Hebrew word of the text, êkāh (“Ah, how!”), which was a characteristic lament. The Septuagint — the mid-third-century BC Greek translation of the O.T. books — entitled it simply Threnoi, “Wailings,” and the later Latin translation added the subtitle: “It comprises the Lamentations of Jeremiah the prophet.”

The text itself dates to the 6th century BC, and the author’s outpourings “included a sorrowful commentary on the sufferings experienced by the Judeans both during and after the siege of Jerusalem [in 587 BC], and also contained a representative confession of national sin.” So writes Derek Kidner, in his brief commentary Jeremiah and Lamentations. Kidner also argues:

As the poems of Lamentations unfold, they make it clear that the real tragedy inherent in the destruction of Jerusalem lies in the fact that it could almost certainly have been avoided. The actual causes of the calamity were the people themselves, who were determined at all costs to pursue the allurements of a false and debased paganism in preference to the high moral and ethical ideals inherent in the Sinai covenant.

The penitent aspect of this book of Scripture make it especially suitable for use during Holy Week, a climactic moment in the Church year when the Church unites — as a holy nation, a people of God’s own possession (I Peter 2:9) — to confess its sins and to recognize that the death of Christ is an effect of our doing those things which we ought not to have done. As the Passiontide hymn — which we sing together — recognizes: “Who was the guilty? Who brought this upon thee? Alas, my treason, Jesus, hath undone thee.”

As early as the eighth century, there are references to the use of readings from Lamentations during Holy Week liturgies. During the 16th century, dozens of the most accomplished composers in Christendom set down rich and moving polyphonic arrangements of the texts that had traditionally been read in these liturgies. Morales, Victoria, Palestrina, Guerrero, and Lassus on the Continent, and in England Byrd and Tallis are among those who set these texts to music.

The Tenebrae Consort’s album includes the music that Thomas Tallis wrote for the first two (of nine) groups of texts used in the Night Office on Maundy Thursday. Despite their traditional liturgical placement, scholars believe that Tallis’s Lamentations settings were composed for private performance as devotional music, not for liturgical use.

Each of the five chapters in Lamentations is a separate poem, the first four written as sophisticated acrostics. As is the case with the Lamentations settings of his contemporaries, Tallis set to music the Hebrew consonant that commences each of the three-line stanzas (Aleph, Beth, Ghimel, etc.). Singing these letters is a bit like singing the numerals that number the verses of a passage from Scripture. But this convention serves to call attention to the fact that this poetry is highly sophisticated in structure.

The first sentence in Lamentations is an observation about the desolation in Jerusalem after its destructive besieging. The declaration has a particular poignancy for us this Lent:

How lonely sits the city that was full of people!

Here is the Tenebrae Consort singing Tallis’s setting of the first two stanzas of the Lamentations. It begins with the words Incipit Lamentatio Ieremiae Prophetae (“Here begins the Lamentation of Jeremiah the Prophet”). The subsequent text is presented below the embedded video. (You can download a score for this section here.)

ALEPH. Quomodo sedet sola civitas plena populo!

ALEPH. How lonely sits the city that was full of people!

Facta est quasi vidua domina gentium;

How like a widow has she become, she that was great among the nations!

princeps provinciarum facta est sub tributo.

She that was a princess among the cities has become a vassal.

BETH. Plorans ploravit in nocte, et lacrimæ ejus in maxillis ejus:

BETH. She weeps bitterly in the night, tears on her cheeks;

non est qui consoletur eam, ex omnibus caris ejus;

among all her lovers she has none to comfort her;

omnes amici ejus spreverunt eam, et facti sunt ei inimici.

all her friends have dealt treacherously with her, they have become her enemies.

Jerusalem, Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum.

Jerusalem, Jerusalem, turn to the Lord, your God.

Tallis’s setting of the next three stanzas of the first poem in the Lamentations opens with an introductory passage that runs for over a minute-and-a-half: De Lamentatione Ieremiae Prophetae (“From the Lamentation of Jeremiah the Prophet”).

GHIMEL. Migravit Judas propter afflictionem, et multitudinem servitutis;

GHIMEL. Judah has gone into exile because of affliction and hard servitude;

habitavit inter gentes, nec invenit requiem:

she dwells now among the nations, but finds no resting place;

omnes persecutores ejus apprehenderunt eam inter angustias.

her pursuers have all overtaken her in the midst of her distress.

DALETH. Viæ Sion lugent, eo quod non sint qui veniant ad solemnitatem:

DALETH. The roads to Zion mourn, for none come to the appointed feasts;

omnes portæ ejus destructæ, sacerdotes ejus gementes;

all her gates are desolate, her priests groan;

virgines ejus squalidæ, et ipsa oppressa amaritudine.

her maidens have been dragged away, and she herself suffers bitterly.

HE. Facti sunt hostes ejus in capite; inimici ejus locupletati sunt:

HE. Her foes have become the head, her enemies prosper,

quia Dominus locutus est super eam propter multitudinem iniquitatum ejus.

because the Lord has made her suffer for the multitude of her transgressions

Parvuli ejus ducti sunt in captivitatem ante faciem tribulantis.

her children have gone away, captives before the foe.

Jerusalem, Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum.

Jerusalem, Jerusalem, turn to the Lord, your God.

In addition to the two Tallis works and a large amount of plainchant from the Sarum Use Compline services, this album also includes John Sheppard’s setting of In manus tuas, which I discussed this past Sunday, since it was traditionally sung on Passion Sunday at Compline. Here is the performance by the Tenebrae Consort of this somber but comforting work. The text is below the embedded video; a score is available here.

In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum.

Into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit.

Redemisti me Domine, Deus veritatis.

You have redeemed me, O Lord, O God of truth.

All of the tracks from this recording seem to be available from YouTube, but it is always a good thing to purchase recordings when possible. As we are repeatedly reminded in Holy Scripture: “The labourer is worthy of his reward.”