The music sung by our parish choir gives preference to music from the Renaissance. There are a number of reasons for this, including the fact that the Anglican musical tradition originates (and sets a trajectory for its further development) during the second half of the sixteenth century. As it happens, this was a remarkably rich time for the composition of choral music. Aesthetic wisdom acquired for over a hundred years was bearing abundant fruit. For composers and musicians, there weren’t many opportunities for musical artistry outside the Church until the seventeenth century. Until then, a critical mass of creative energy was focused on writing for voices, often without instrumental accompaniment, and usually for use in liturgical settings.

Much of the music composed during this era was polyphonic, that is, it involved multiple musical lines that were connected with each other in such a way that (miraculously) each voice was simultaneously independent of the others, and yet each voice received its meaning from its complex relationship to all the other voices. I like to call polyphony “trinitarian” music, since that one-in-many-in-one character — mutual co-inhabiting — seems to me to imitate the dynamic of life within the members of the Trinity.

Another theological word that is more often used to describe this music is “glory.” For example, Alex Ross, music critic for the New Yorker, has written that “Renaissance polyphony does for the ears what the Sistine Chapel does for the eyes, giving lyric shape to divine power.” It is sad that modern listening habits seem to have rendered many people deaf to this glory, even though they recognize it in visual arts of the Renaissance, including architecture.

One of the most accomplished ensembles specializing in choral music from the Renaissance is a British ensemble named Stile Antico. The historical precedent for their name is explained on their website:

The term “stile antico,” pronounced STEE-lay an-TEE-co, literally means “old style.” It was coined during the seventeenth century to describe the style of Renaissance church composition epitomised by the music of Palestrina — polyphonic and imitative in texture, even in rhythm, strictly controlled in its use of dissonance — as opposed to the modern developments in the works of Monteverdi and his contemporaries. Over the centuries, the “stile antico” came to be seen as an ideal of musical purity, and composers such as Beethoven, Schumann, Liszt and Bruckner studied it as part of their training. It is still taught in universities today.

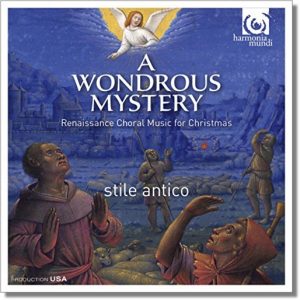

In 2015, Stile Antico released an album of Christmas music called A Wondrous Mystery: Renaissance Choral Music for Christmas. In their impressive and growing catalogue, it joined their 2010 seasonal recording, Puer natus est: Tudor Music for Advent and Christmas. That album (which I also recommend) featured music by William Byrd and Thomas Tallis, as well as the lesser known Robert White and John Sheppard.

A Wondrous Mystery is a more diverse collection, including vibrant works by Michael Praetorius, Hieronymus Praetorius, and Hans Leo Hassler. A thread running through the entire program of the album is the presence of a motet and mass by Jacob Clemens non Papa (c.1510-1555). The motet is Pastores quidnam vidistis (“Shepherds, what have you seen”). In the mass — Missa Pastores quidnam vidistis — Clemens non Papa developed distinctive musical features from the motet. In a sense, the mass is a fulfillment of the possibilities latent in motet. This common compositional practice — basing a mass on an earlier work — seems especially apt in a Christmas work, as it echoes the pattern of the Incarnation’s fulfillment of possibilities, human and redemptive.

One of the most intriguing pieces here is Mirabile mysterium by Jacob Handl (1550-1591). The text to this motet is an antiphon sung at Lauds on the Feast of Circumcision: “A wondrous mystery is declared today, an innovation is made upon nature; God is made man; that which he was, he remains, and that which he was not, he takes on, suffering neither commixture nor division.” Handl uses a series of unpredictable harmonic progressions to capture the sense that something disorienting — or, better, re-orienting — is happening in the Incarnation, and thus, in the world. (In the notes that accompany this recording, the adjectives “astonishing” and startling” are used descriptively.) At the end of the work, the Latin phrase “non commixtionem passus” (“suffering no commixture”) is repeated over and over, underscoring this important fact about Christ’s two natures. A wondrous mystery indeed.

The ensemble wisely placed a more comforting and warmer work in the program hard on the heels of Handl’s mystical exploration: a charming motet by Johannes Eccard (1553-1611), Über’s Gebirg Maria geht (“Over the mountain Mary goes”), describing the Virgin’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth. (Our choir has a related piece by Eccard scheduled for February, describing Mary’s presentation of Jesus at the Temple.)

Those are a few of the highlights of this album, on which all of the performances are vivid, sensitive, and, well, glorious. You may listen to excerpts from several of the tracks on the Stile Antico website or at Soundcloud.

You can read about an earlier recording by Stile Antico in “A Tudor tutorial.”