by Ken Myers

[This article originally appeared in the May/June 2017 issue of Touchstone magazine.]

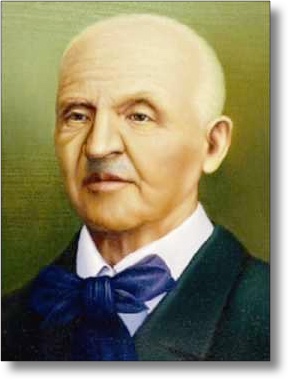

Few composers have prompted as intense and diverse a chorus of responses as Anton Bruckner (1824-1896). His contemporary Johannes Brahms dismissed Bruckner’s massive symphonies as “a swindle that will be forgotten in a few years.” On the other hand, more than a few years later, Ludwig Wittgenstein would remark: “I don’t believe a note of Gustav Mahler. I believe every note of Anton Bruckner.” While some listeners are attracted to his music at first hearing — an attraction that deepens with time — others adamantly deny that there’s anything there worth loving. In 2012, Jessica Ducken, a music journalist for The Independent, wrote a cranky column entitled “Anton Bruckner makes me lose the will to live,” complaining that she has tried to learn to like Bruckner’s music for 30 years and never succeeded. (Doth she protest too much? And why, one wonders.)

Most of the fuss about Bruckner usually concerns his symphonies, which are demanding even for the most sympathetic listener. His nine symphonies have been likened to “cathedrals in sound” because of their monumental scale and their sense of huge, mysterious, and dark spaces punctuated by shafts of light. They also convey the apparently paradoxical moods sometimes experienced when one walks through (or prays in) a cathedral: “rigor and opulence, simplicity and ecstasy, anxiousness and solemnity follow each other in quick succession,” writes musicologist Constantin Floros. “Add to that a fairly singular synthesis of the archaic and the modern.” Echoes of the confident security of plainchant and Palestrina are juxtaposed with nervous harmonic meanderings that disturb and disorient.

Musical Side Chapels

The paradoxes of Bruckner’s style are also evident in his sacred motets. If the symphonies are like cathedrals, these short settings of traditional liturgical texts are like side chapels that focus meditation more intimately but with no loss of transcendence. Consider, for example, the stately Locus iste, an a cappella rendering of a text traditionally sung at the dedication of a church: “This place was made by God, a priceless mystery; it is without reproach.” Bruckner’s motet was written in 1869 for the dedication of a new chapel in the cathedral in Linz.

The piece commences with the Latin text meaning “This place was made by God,” sung in short, rhythmically regular phrases in straightforward and simple harmonies. The affirmation of the origins of the place is echoed in patterns of musical expression that suggest the regularity and sturdiness of good brickwork. On the words inaestimabile sacramentum, “a priceless mystery,” the basses — entering with a low and commanding intonation — introduce a much more turbulent procession of harmonies that accompany ascending melodic lines. The ominous sound of those low voices and the harmonic tension are a signal that the mysteriousness of what happens in this secure place will be surprising, perhaps even unsettling. (I’m reminded of Annie Dillard’s remark that if we really understood the dangerous construction work being done during worship, we’d wear hard hats.) This phrase is followed by the quiet assertion irreprehensibilis est, “it is without reproach,” repeated four times by the three upper voices in descending lines of chromatic harmony that finally resolves on a stable chord which anticipates the recapitulation of the opening phrases. After this gently underlined reminder of the authority and security of this sacred space, we return to the opening affirmation of the Builder and His workmanship.

Throughout the piece (which typically takes less than three minutes to perform), the reassuring steadfastness present in the holy space in Linz — and in every other church — is constantly evoked by the serene, regular rhythmic flow, which is sustained even through five beats of complete silence near the end of the short piece. Critic Stephen Johnson has suggested that Locus iste conveys a “mysterious sense of ‘rightness’,” perhaps because the ascetic simplicity of the form of the work suggests an opening into something much larger. If a church building is worthy of its vocation, it must invite wonder at the magnificence of the mysteries it houses, but such wonder will lead more fittingly to silence than applause.

Here is a performance of Locus iste by The Sixteen, conducted by Harry Christophers.

Another of the more celebrated motets is Os justi, composed in 1879 and dedicated to Ignaz Traumihler, the choirmaster at the Augustinian monastery of St. Florian in Upper Austria, a holy place with a profound significance in Bruckner’s life. When Bruckner was only 12 years old, his father died of consumption, and on the day of his death, his mother took him to the nearby monastery, asking the prior if her son could be taken in as a chorister. This was the beginning of a thoroughly formative musical and spiritual pilgrimage for Bruckner, whose piety was notable among nineteenth-century artists. “In an era when agnosticism gripped the thoughts of intellectuals and artists throughout Europe,” writes biographer Derek Watson, “he remained an unquestioning believer.”

The text to Os justi (“the mouth of the righteous”) is from Psalm 37 and Psalm 89. The opening line continues “and his tongue speaks what is just.” The piece was commissioned by Traumihler for the feast of St. Augustine. As choirmaster, Traumihler was an active member of the Cecilian Movement, a mid-century crusade centered in Germany dedicated to purifying liturgical music by recovering the simple virtues of plainchant and a cappella polyphony. When Bruckner sent Traumihler the score for Os justi, he described the virtues that he believed would appeal to the Cecilian: “I should be very pleased if you found pleasure in the piece. It is written without sharps and flats, without the chord of the seventh, without a six-four chord and without chordal combinations of four and five simultaneous notes.” Despite his self-imposed straitjacket (or perhaps because of it), Bruckner achieves a remarkable emotional power in Os justi. When the Choir of St. Bride’s Church, Fleet Street assembled their album of Bruckner’s motets, they saw fit to place it as the first work in the collection.

We know from documentary evidence that Bruckner’s music was an expression of his intense faith, a faith that involved agonizing emotional struggle. I think we can also hear the presence of that faith in the music itself, especially in these motets. Stephen Johnson finds it remarkable that “this neurotic, lonely, often tortured and insecure man also carried within himself that sense of some unfathomable deeper purpose.” In that description one can’t help but recognize the profile of many servants of truth and beauty.

The All Saints choir frequently sings Bruckner’s setting of Pange lingua, Thomas Aquinas’s Eucharistic hymn. Below is a performance of this motet sung by the Dresdner Kreuzchor, conducted by Martin Flamig.

Our choir has also sung Bruckner’s D-major setting of the Tantum ergo. It is sung below by the Choir of St. Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, conducted by Robert Jones with Matthew Morley at the organ.

You can hear 15 of Bruckner’s motets sung by the Choir of St. Bride’s Church via this YouTube playlist.