On this page:

The text: comfort in contentment

The tune: confidence in a minor key

Some of J. S. Bach’s settings of this tune

Felix Mendelssohn’s cantata, Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten

[Lawrence L. Lohr wrote an informative article in The Hymn (Vol. 49, No. 3, July 1998) titled “‘If thou but suffer God to guide thee’: The Journey of a Lutheran Hymn.” You may read and download a copy of that article here.]

Origins of the text

A hymn text and a chorale melody are both known by the name Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten (“Whoever lets our beloved God rule”). Both are the work of Georg Neumark (1621-1681). According to the story behind the text, Neumark completed his studies at the Gymnasium in Gotha in 1641 and was traveling with friends bound for Königsberg where he hoped to enroll at the university. But on the road, he and his companions were attacked by bandits. Neumark was robbed of everything he owned save his prayerbook and a small amount of money sewn into the lining of his clothing.

Bereft of funds for his studies he set out to find employment, searching for a job in Magdeburg, Lüneburg, Winsen, and Hamburg, but to no avail. He expanded his search to the city of Kiel, where he was befriended by the chief pastor, who kindly recommended Neumark for a position as a tutor for the family of a judge. Out of gratitude for relief from need and anxiety, Neumark wrote a seven-stanza hymn, celebrating the virtues of contentment and trust in God.

1. Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten

Whoever lets only the dear God reign

Und hoffet auf ihn allezeit,

and hopes in him at all times,

Den wird er wunderlich erhalten

he will preserve in a marvelous way

In allem Kreuz und Traurigkeit.

in every cross and sadness.

Wer Gott, dem Allerhöchsten, traut,

Whoever trusts in almighty God

Der hat auf keinen Sand gebaut.

has not built upon sand.

2. Was helfen uns die schweren Sorgen?

How much do heavy worries help us?

Was hilft uns unser Weh und Ach?

How much do our ‘woe and alas’ help us?

Was hilft es, daß wir alle Morgen

How much does it help, that every morning we

Beseufzen unser Ungemach?

sigh over our misfortune?

Wir machen unser Kreuz und Leid

We make our own cross and sorrow

Nur größer durch die Traurigkeit.

only greater through sadness.

3. Man halte nur ein wenig stille

We should only keep quiet for a little while

Und sei nur in sich selbst vergnügt,

and be content in ourselves

Wie unsers Gottes Gnadenwille,

in accordance with the gracious will of our God,

Wie sein’ Allwissenheit es fügt.

with how his omniscience arranges.

Gott, der uns sich hat auserwählt,

God who has chosen us for himself

Der weiß auch gar wohl, was uns fehlt.

knows very well what we need.

4. Er kennt die rechten Freudenstunden,

He knows the right hours of joy,

Er weiß wohl, wann es nützlich sei.

he knows well when it will be useful:

Wenn er uns nur hat treu erfunden

if he has only found us faithful

Und merket keine Heuchelei,

and notices no hypocrisy,

So kommt Gott, eh’ wir’s uns versehn,

then God comes, before we expect

Und läßet uns viel Gut’s geschehn.

and allows much good to happen to us.

5. Denk nicht in deiner Drangsalshitze,

Do not think in the heat of your suffering

Daß du von Gott verlaßen sei’st,

that you have been abandoned by God

Und daß der Gott im Schoße sitze,

and that sitting in God’s lap is enjoyed by

Der sich mit stetem Glücke speist.

someone who enjoys constant good fortune.

Die Folgezeit verändert viel

Time’s course brings about many changes

Und setzet jeglichem sein Ziel.

and appoints to each person his goal.

6. Es sind ja Gott sehr leichte Sachen

For God these are easy matters

Und ist dem Höchsten alles gleich,

and the Almighty can equally

Den Reichen arm und klein zu machen,

make the rich man poor and little,

Den Armen aber groß und reich.

while he makes the poor man rich and great.

Gott ist der rechte Wundermann,

God is the true worker of wonders

Der bald erhöhn, bald stürzen kann.

who can soon raise up, soon cast down.

7. Sing, bet und geh auf Gottes Wegen,

Sing, pray and go on God’s way,

Verricht das Deine nur getreu

Perform your part only faithfully

Und trau des Himmels reichem Segen,

and trust in the rich blessing of heaven,

So wird er bei dir werden neu;

then he will be with you anew;

Denn welcher seine Zuversicht

For who places his confidence

Auf Gott setzt, den verläßt er nicht.

in God, he does not abandon.

[English Translation by Francis Browne,

from the Bach Cantatas Website]

For many years, this hymn was sung in German Lutheran churches on the Fifth Sunday after Trinity, perhaps because its resonates so well with the promise in that day’s Epistle reading. In that reading’s excerpt from I St. Peter 3, we are comforted with the knowledge that “the eyes of the Lord are over the righteous, and his ears are open to their prayers.”

Most English-language hymnals feature an 1863 translation of this hymn by Catherine Winkworth (1827-1878). In older hymnals, the first line is rendered “If thou but suffer God to guide thee,” the word “suffer” being used in its somewhat antiquated sense meaning “permit.” More modern (and timid) hymnal editors sometimes modify Winkworth’s translation to “If thou but trust in God to guide thee,” or “If you will trust in God to guide you.”

This hymn is not in the 1940 Hymnal, but a pdf copy of four of the stanzas as sung in our parish may be downloaded here.

The tune: confidence in a minor key

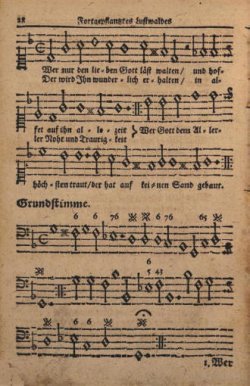

The tune to which this hymn has been sung since the 17th century — in German and English and likely in many other languages (it was sung in Danish in the movie Babette’s Feast) — was first published in 1659. It appeared then in a collection of hymns by Neumark.

Like many chorale melodies, Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten has an A-A-B structure, 3 phrases with the first and second phrases identical. The first two phrases are in a minor key. The first half of the final phrase, which contains the highest notes in the tune, are in a major key, before descending to the final 8 notes and returning to the major key. The overall effect of the melody is both haunting and hopeful, which may account for its presence in dozens of compositions by many composers from the 17th century to the present.

Below is Andrew Remillard’s rendition of this hymn on piano.

Some of J. S. Bach’s settings

Johann Sebastian Bach clearly admired this tune and its associated text. At least 8 of Bach’s cantatas feature this chorale melody. It was also employed in a number of his compositions for solo organ. Here is a chorale harmonization that may have been included in one of Bach’s many lost cantatas. (The score for this distinctive setting may be viewed here.)

Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten, BWV 434, sung by Agnes Giebel, Marie-Luise Gilles, Bert van t’Hoff, and Peter Christoph Runge, with Anner Bylsma on cello and Gustav Leonhardt at the organ.

Before listening to how Bach used this tune in a few of the cantatas, here are several of the organ settings.

Chorale prelude BWV 642,

from the “Little Organ Book,”

Luca Raggi, organ

Chorale prelude BWV 647,

from the Schübler Chorales,

Marie-Claire Alain, organ

Chorale prelude BWV 690,

from the Kirnberger Chorales,

Wolfgang Rubsam, organ

Chorale prelude BWV 691,

from the Kirnberger Chorales,

Dorien Schouten, organ

Within Bach’s cantatas, there are numerous variations on this chorale melody, often using the text from Neumark’s hymn. For example, near the end of the cantata Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis (“I have great heaviness in my heart,” BWV 21), is a choral movement which opens with soloists repeating the words “Sei nun wieder zufrieden, meine Seele, denn der Herr tut dir Guts” (“Be satisfied again now, my soul, for the Lord does good to you”). After several repetitions of this affirmation, the entire tenor section of the choir begins singing the second stanza from Neumark’s hymn to the tune he created for it:

What help to us are heavy sorrows

What help to us are our ‘woe’ and ‘alas’?

What does it help, that we every morning

sigh over our troubles?

We make our cross and suffering

only greater through sadness.

After the tenors finish these words, the soloists continue repeating that single line while the sopranos sing the hymn’s fifth stanza:

Do not think in the heat of your distress

that you have been abandoned by God

and that that man sits in God’s bosom

who always feeds on good fortune.

The course of time changes many things

and appoints his end to everything.

The chorus Sei nun wieder zufrieden, meine Seele is performed here by the Monteverdi Choir with the English Baroque Soloists, conducted by John Eliot Gardiner. The soloists are Katherine Fuge, soprano; Robin Tyson, alto; Vernon Kirk, tenor; and Jonathan Brown, bass

The Monteverdi Choir and the English Baroque Soloists, with Katharine Fuge, soprano; Robin Tyson, alto; Vernon Kirk, tenor; and Jonathan Brown, bass, conducted by John Eliot Gardiner

This compelling tune is used very dramatically in a cantata Bach composed in 1726 for the 16th Sunday after Trinity. The text used in the cantata is from a hymn written in the late 17th century by Ämilie Juliane, Countess of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt. Her 12-stanza text expresses somber confidence in God’s mercy in the face of death. Bach used the first stanza of this hymn in the opening chorus of Wer weiß, wie nahe mir mein Ende? (“Who knows how near my end is to me?” BWV 27). Bach punctuates the full choir’s presentation of the chorale melody with dramatic recitatives from three soloists. (The text is here.)

The Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir, with Johannette Zomer, soprano; Annette Markert, alto; and James Gilchrist, tenor, conducted by Ton Koopman.

Bach’s most expansive adaptation of this hymn is in the cantata that takes its name from Neumark’s poem, Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten (BWV 93). Bach rarely includes the same tune in each movement of a cantata, but he did so in this work, which was composed for the Fifth Sunday after Trinity, the week when Neumark’s hymn was traditionally sung in Lutheran congregations.

Commenting on this remarkable cantata, conductor John Eliot Gardiner writes:

Bach seems to be delving back to his childhood roots, not just on account of this cherished hymn, not just on account of this cherished hymn but in the way he structures it in two of the movements (Nos 2 and 5), based on the catechismal question-and-answer formula by which he learnt all his lessons. So he takes a stanza of Neumark’s hymn and announces it line by line: ‘What can heavy cares avail us? What good is our woe and lament?’, always lightly embellished by the soloist, and then interrupts it in free recitative by means of an answering text: ‘They only oppress the heart with untold agony and endless fear and pain’, and so on, as in a medieval trope. It means that one needs to be constantly alert to Bach’s free treatment of Neumark’s chorale (or else utterly familiar with it, as was his congregation) in order to follow the astonishing ways he varies, decorates, abridges or repeats it — all for rhetorically expressive ends. In the opening fantasia the four vocal concertisten lead off in pairs singing an embellished version of all six lines of the hymn before it is given ‘neat’ in block harmony by the (full) choir, the lower voices then fanning out in decorative counterpoint. In the central movement (No.4) of this symmetrically conceived work, the hymn stands out in its pure form, like gold capitals in a medieval missal. Its wordless delivery is given by unison violins and violas, while the soprano and alto ornament a lyrical contraction of the tune. In the two arias the disguise is even subtler. It re-emerges paraphrased in the string-accompanied tenor aria (No. 3). If we wonder why the steps of this elegant passepied are halted every two bars, the tenor soon makes it clear: ‘Remain silent for a while’ (‘Man halte nur ein wenig stille’) – and listen to what God has to say. There is a further tease in the final aria, ‘Ich will auf den Herren schaun’ (No.6). In their carefree exchanges, the soprano and oboe seem to assure us that for the first time in the cantata, we are in a chorale-free zone. Then at the mention ‘He is the true miracle-worker’ (‘Er ist der rechte Wundermann’) in comes the hymn tune, unaltered for its Abgesang. One wonders whether this profligacy of invention and wit was relished or wasted on Bach’s first listeners.

The text to the entire cantata is here, and below is a performance by Collegium Vocale Ghent, conducted by Philippe Herreweghe. The soloists are Agnès Mellon, soprano; Charles Brett, alto; Howard Crook, tenor, and Peter Kooy, bass.

Felix Mendelssohn’s cantata Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten

In 1829, Felix Mendelssohn (channeling Bach, as he sometimes did) composed a 4-movement cantata based on Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten. The performers here are the Stuttgart Chamber Chorus and Orchestra, conducted by Frieder Bernius. The recording is from a multi-volume set of Mendelssohn’s church music.