by Ken Myers

[This article originally appeared in the January/February 2017 issue of Touchstone magazine.]

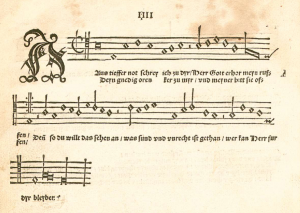

The Reformation’s lasting influence on the music of the Church begins with the publication in early 1524 of Etlich Cristlich lider Lobgesan, the first Lutheran hymnbook. Also known as the Achtliederbuch, the Hymnal of Eight, it contained the German texts for just eight hymns (four of which were by Luther) and only five tunes. One of the texts — printed under the heading “Der Psalm de Profundis” — was Luther’s paraphrase of Psalm 130. Better known by the first several words in the German, “Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu Dir,” this hymn has been translated into English numerous times, sometimes as “From deepest woe,” or “From depths of woe,” or — following the Latin more literally — “Out of the depths.”

From deepest woe I cry to thee;

Lord, hear me, I implore thee!

Bend down thy gracious ear to me;

I lay my sins before thee.

If thou rememberest every sin,

if nought but just reward we win,

could we abide thy presence?

Luther’s tune

The Achtliederbuch did not include a new melody to accompany this text, a condition that was remedied later in 1524 when a second Lutheran hymnal was published. The Erfurt Enchiridion contained twenty-five hymns (eighteen by Luther), again including “Aus tiefer Not,” this time with a fresh tune attached, a melody adapted by Luther and his colleague Johann Walter from a fifteenth-century predecessor.

This haunting melody is in the Phrygian mode (play the white notes on a piano from E to E, and notice that half-step between the first and second notes), a minor mode that Luther preferred to use for penitential texts. The first note is held twice as long as the subsequent notes in the opening phrase, and then the melody jumps down to begin the word tiefer, “deeper,” a perfect fifth lower than the first note. This is a dramatic interval to experience at the beginning of a melody, and it thus forces singers of this hymn to experience (if only melodically) the depth of sinful shame.

The second, fourth, and final lines of the seven-line tune also reinforce a downward movement, like that of heads bowing. Luther must have believed that congregations singing Psalm 130 needed to be musically reminded of the nature of true penitence. In commenting on this Psalm, he once noted that “We are all in deep and great misery, but we do not feel our condition.” That opening interval might just stimulate the appropriate feeling.

The tune became known as AUS TIEFER NOT (you’ll find it so designated in a good hymnal’s index of tunes), and was linked to Psalm 130 in settings by many composers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Lutheran liturgies — especially services for funerals — used the hymn regularly; it was sung at Luther’s own funeral in 1546.

Later adaptations

In 1724, exactly two-hundred years after this hymn was first published, J. S. Bach composed a cantata (BWV 38) using this melody and two of Luther’s five verses for the opening and closing movements of Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu Dir. Conductor John Eliot Gardiner has described the final chorale of BWV 38 as “terrifying in its Lutheran zeal.” That chorale, with Luther’s penitent tune, begins on a disorienting dissonant chord (an inverted dominant 7th) that forcefully reinforces the torment expressed in the Psalm’s urgent and contrite plea for undeserved forgiveness.

J. S. Bach, Cantata BWV 38: Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir,

performed by Collegium Vocale Gent, Philippe Herreweghe, conductor

A little more than a hundred years after Bach’s cantata was written for his congregation in Leipzig, the young Felix Mendelssohn composed a number of works based on chorale texts and melodies from the Lutheran tradition. The first was written shortly after his landmark revival of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in 1829, just after Mendelssohn’s twentieth birthday. That year his father encouraged him to embark on the sort of “grand tour” then customary for European gentlemen. In Felix’s case it comprised a three-year excursion through England, Bavaria, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, and France.

While residing in Vienna, in the middle of 1830, young Felix became impatient with the “frivolous dissipation” of the Viennese and devoted himself to composing some works of sacred music, including a three-movement cantata based on Paul Gerhardt’s 1656 “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” (“O sacred Head sore wounded”), a chorale which Bach used no fewer than six times in the St. Matthew Passion. Mendelssohn’s setting displays his willingness to honor earlier musical styles — of Bach, even of Palestrina — in ways that were unfashionable in a time and place anxious about fidelity to the forward-looking posture of the Enlightenment. For Mendelssohn, however, as musicologist Georg Feder has noted, “no viewpoint would be rejected solely on the basis of its age. For him, progress could also include falling back on older means.”

Those older means sometimes involved a creative engagement with Lutheran chorale texts and tunes. Shortly before leaving Vienna for Italy, his friend and fellow Bach enthusiast Franz Hauser gave Mendelssohn a volume of Lutheran hymns. Within the next two years, he produced settings of five of them. One of those was a five-movement setting of Luther’s Aus tiefer Not. It is one of Mendelssohn’s most Bachian compositions, constructed symmetrically with chorales in the first and last movement, a tenor aria with chorus in the center, and two contrapuntal choruses in sections two and four.

Perennial wisdom

Hearing this piece today, Luther’s pastoral and theological wisdom in selecting this tune for this text becomes obvious. Almost five hundred years since that 1524 hymnal was published, we can experience this compelling melody with the historical awareness of how — with the help of Bach, Mendelssohn, and others — it has moved generations of believers to a recognition of their deep need, and of the steadfastness of the One who will redeem his people from all their iniquities.

Felix Mendelssohn’s Aus tiefer Noth schrei’ ich zu dir, Op. 23, No. 1

performed by the Chamber Choir of Europe, Nicol Matt, conductor