In 2015-2016, conductor and musicologist Christopher Page gave a series of lectures titled “Music, Imagination, and Experience in the Medieval World.” They were sponsored by Gresham College, which was founded in 1597 and has been providing free lectures within the City of London for over 400 years.

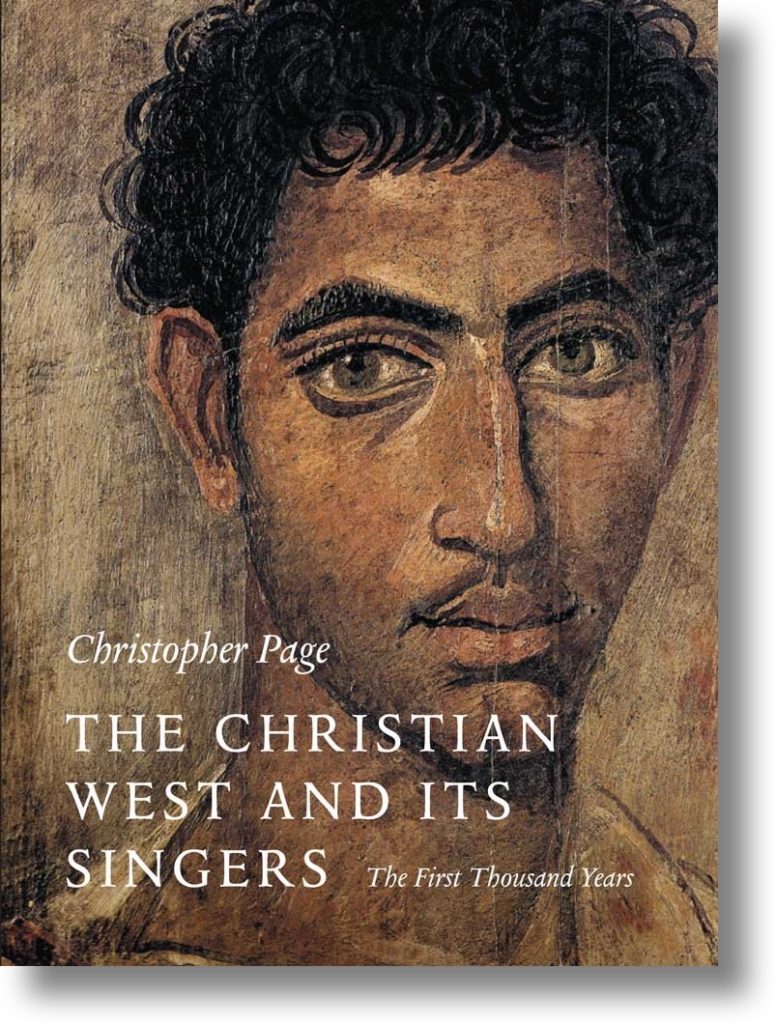

In 2016-2017, Page gave a series of lectures that explored an earlier era of the Church’s experience with music. Titled “The Christian Singer from the Gospels to the Gothic Cathedrals,” these six lectures presented material from Page’s 2010 book The Christian West and its Singers: The First Thousand Years (Yale University Press). Recordings of these six lectures are presented below. An interview with Page about his book may be heard here.

Lecture 1: The Music of the First Christians

Early in the second century a Roman governor interrogated a group of Christians to satisfy himself that they had not offended against his recent edict banning clubs that might acquire a political slant. The Christians told him that they said that they convened before dawn on Sundays, when they were accustomed to sing a hymn of praise, and that they met subsequently to share a common meal. Perhaps to confute the rumor that they and their co-religionists indulged in cannibalism, the prisoners insisted that they ate perfectly innocent food when they gathered. Like many others in the first and second centuries, the governor thought the Christians very strange. So they were in many respects, but they were not so strange that they repudiated the use of ritual song. We begin our survey with the music of the first Christian communities.

Lecture 1: The Music of the First Christians

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 2: Towards a Ministry of Singing

At some time in the fourth century some bishops assembled for a synod in a city whose site is now in Turkey. Today, the place where they met retains little of the grandeur that made it an appropriate choice for such a gathering; there are only broken walls in a coarsened landscape, grazed by sheep, to recall the colonnades and forum of the ancient city with its basilicas. In their deliberations, the bishops identified for the first time in Christian history, an actual ministry of song. They decreed that Only regularly appointed singers capable of reading from parchment, should be allowed to ascend the pulpit from now on and sing in churches. This lecture will build on this foundational moment in Christian musical history.

Lecture 2: Towards a Ministry of Singing

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 3: Schooling Singers in the Cathedrals

A singer in a church of 450-650 was generally appointed in the same way as a gravedigger – too lowly to demand the bishop’s attention. While the task of selecting a reader required the bishop to hear reports of the candidate’s reputation for honest living and a presentation in a public ceremony, a singer who was often charged to voice the same divine words but in song could be admitted without any references or any codified rite of induction. Yet arrangements were increasingly made to school singers in the great metropolitan churches of the West, as will be demonstrated.

Lecture 3: Schooling Singers in the Cathedrals

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 4: Roman Singing and its Influence Across Europe

Amidst the increasingly material penury of the early medieval world, Rome and Byzantium (that is to say New Rome, now Istanbul) offered a continuing example of opulence and luxury that was expressed in worship with expensive textiles, precious metals and sonorous titles of office, including now the singer or cantor, that proclaimed supreme honour and eternal victory through liturgy. In the Western kingdoms, to maintain rich services, with a staff of good singers, was one of the ways in which a king came into his inheritance as surely as moving into the old governor’s palace. In this lecture we shall explore what the singing of Rome meant far afield: in northern England, Ireland, Spain, and Germany.

Lecture 4: Roman Singing and its Influence Across Europe

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 5: The Christian Singer: Charlemagne and Beyond

In the year 754 the first pope ever to cross the Alps came to a small chapel in what is now northern France and prostrated himself before the king of the Franks, beseeching him for military aid. The pope came with singers from the Roman song school. When he and the king signed “treaties of peace” together the foundations were laid for what has long been known as Gregorian (or better “Frankish-Roman”) Chant. This is the music of a transalpine Western Europe beginning o revive, albeit very slowly, after the withdrawal of Roman imperial power. No activity marked this broader horizon more potently, or more often, than the daily celebration of Gregorian chant by priests, deacons and singers.

Lecture 5: The Christian Singer: Charlemagne and Beyond

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.

Lecture 6: Singers in the Making of Europe

By the twelfth century the West could be imagined as a soundscape of Latin plainsong and be given a name: Latinitas. The Gregorian chants for the Mass figured prominently in this body of shared material, and were spread by many different methods of colonization and conquest. This was both internally by the foundation of new houses in abandoned or waste areas and externally by crusade in Spain, eastern Europe, and Livonia. The singers of the Latin churches were therefore masters of an art that belongs with other aspects of medieval culture that helped to impel what may be called “the making of Europe.”

Lecture 6: Singers in the Making of Europe

A transcript for this lecture is available near the bottom of this page.