by Ken Myers

[This article originally appeared in the March/April 2018 issue of Touchstone magazine.]

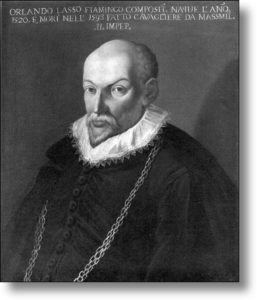

Among musically knowledgeable listeners, even those who admire the music of the high Renaissance, the work of Orlande de Lassus is woefully unfamiliar. It was not always so. During his lifetime, in the second half of the sixteenth century, Lassus was easily the most famous composer in Europe. With contemporaries that included Palestrina, Victoria, and Byrd, such fame is a remarkable tribute to his artistic accomplishments. Another contemporary, the celebrated French poet Pierre de Ronsard, hailed Lassus as one “who like a bee has sipped all the most beautiful flowers of the ancients and moreover seems alone to have stolen the harmony of the heavens to delight us with it on earth, surpassing the ancients and making himself the unique wonder of our time.”

The neglect of his work in our time may be a function of the fact that his genius renders him (in the judgment of music historian Richard Taruskin) “a blessedly unclassifiable figure who sits uncomfortably in any slot.” Born in 1530 (or 1532), Lassus was honored in his day for unsurpassed musical versatility, adapting his compositional skills to a wide range of languages, aesthetic forms, and performance settings. “In every vocal genre of his time,” writes musicologist Ignace Bossuyt, “sacred or profane, he was like a fish in water: Latin motets, Masses, lectiones, Magnificat settings, and Lamentations, French chansons, Italian villanelles and madrigals, German lieder, all flowed effortlessly from his prolific pen.” His very name was the site of protean cosmopolitanism; born at Mons in Hainaut (a Franco-Flemish province) and baptized “Roland de Lassus,” he was (and is) known variously as Orlando di Lasso, Orlandus Lassus, Orlande de Lattre and Roland de Lattre (I’ve adopted the New Grove Dictionary and Wikipedia convention of Orlande de Lassus).

Lassus was prolific as well as gifted. His sacred repertoire alone includes about 60 Masses and 101 settings of the Magnificat, as well as hundreds of motets. Many of these works were composed during his tenure as court and chapel musician to the dukes of Bavaria in Munich, whom he served from 1556 until his death in 1594. His expressive abilities in setting sacred texts were surely aided by his experience with the hundreds of elegantly crafted (and wildly popular) secular songs he composed through his lifetime.

The Penitential Psalms

In the late 1550s, Lassus composed a cycle of seven motets, published later as Psalmi Davidis Pœnitentiales. Based on the texts of seven psalms with penitential themes — texts frequently employed during Lent both in liturgies and in private devotion — Lassus brilliantly conveyed in these motets the spirit of lament and dejection that accompanies one’s recognition of unworthiness before God. His Flemish contemporary, Samuel Quickelberg, marveled that in these settings, Lassus captured “the intensity of the different emotions by conjuring up the subject as if it were enacted before one’s eyes” so “that one may wonder if it is the sweetness of the emotions which more adorns the plaintive melodies, or the melodies the emotions.”

As did Victoria, Palestrina, and Byrd, Lassus understood that the inner tensions of sorrow are best communicated contemplatively, not with the flamboyant display that some of his Baroque successors would later exploit. Sighs too deep for words (and the interior affections that evoke such sighs) can be echoed in well-crafted melodic lines and subtle (and often surprising) harmonic shifts.

The seven psalms Lassus chose for this cycle are 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, and 143. Each psalm is rendered in its entirety, each verse set as a “mini-motet” with a closing cadence, and vocal forces vary from verse to verse, employing from two to five voice parts. These are not works suitable for big choirs; the intimacy and clarity of expression would likely be lost with more than a few singers per part. The 2003 recording by the a cappella Collegium Vocale Gent, conducted by Philippe Herreweghe, demonstrates how the humility present in both texts and music are served with a lean and disciplined choral soundscape.

Psalmi Davidis Pœnitentiales

Collegium Vocale Gent, conducted by Philippe Herreweghe

The Tears of St. Peter

Psalmi Davidis Pœnitentiales was a relatively early work for Lassus, completed before he turned 30. In the last months of his life, Lassus wrote a cycle of “spiritual madrigals,” a unique collection known as the Lagrime di San Pietro, “The Tears of St. Peter.” Early in his career, Lassus had established a reputation for his mastery of the Italian madrigal (the word comes from the same root as “maternal,” indicating a song in the mother tongue rather than Latin). Madrigals were typically not religious, though often serious (the poetry of Petrarch was a favorite early source of texts). But there were also madrigals with devotional texts, encouraged by the Counter-Reformation as a means of nurturing piety outside the formal confines of the liturgy.

In 1560, the Italian Petrarchian poet Luigi Tansillo published a set of 42 eight-line stanzas (ottave rime) expressing in agonizing slow-motion the remorse and repentance felt by St. Peter after his betrayal of Christ. Between 1593 and 1594, Lassus set twenty of these Italian stanzas to music. To complete Lagrime di San Pietro (and to assemble a total of twenty-one segments in the large work, a number not incidentally divisible by both seven and three), Lassus added a Latin motet. The text of Vide homo, quae pro te patior conveys in the first person the pain experienced by Christ on the cross because of Peter’s denial, a pain greater than that caused by the nails that pierced his hands and feet. Each of these twenty-one short pieces is arranged for seven voices, an uncommon array of musical forces but fitting in light of the association of the number seven with suffering (the seven wounds of Christ, the seven last words on the cross, the seven sorrows of Mary, and so forth). In late May of 1594, Lassus dedicated the newly completed work to Pope Clement VIII. Three weeks later, the composer died.

The music in Lagrime di San Pietro displays that quality described by Lassus’s Parisian friend, Adrien Le Roy, as “pressus et limatus,” concise and refined. Every note matters, every pause is poignantly expressive. The austerity of the musical style concentrates the emotional urgency of the poetry. One wonders whether Lassus, while striving to represent in sound the interior life of this headstrong but chastened disciple, recalled his own creative engagement almost forty years earlier with those seven penitential Psalms. Did he connect St. Peter with David? Meditative attention to these two cycles of motets leads one to wonder also if St. Peter recalled the texts of those same psalms during the dark, tormented hours before dawn on the first day of a new and miraculous week.

Below is one of many performances of Lassus’s Lagrime di San Pietro conducted by Philippe Herreweghe. The text of the 21-stanzas set by Lassus can be read here.

Lagrime di San Pietro

Sopranos: Maria-Cristina Kiehr, Hana Blazikova; Altos: Thomas Hobbs, Chris Watson; Tenor: Stephan MacLeod; Basses: Tore Denys; Peter Kooij; Directed by Philippe Herreweghe