Our service opens with “Praise, my soul, the King of Heaven,” a hymn by Henry Francis Lyte (1793-1847), a devout Anglican priest and a sensitive and accomplished poet. The hymn’s affirmation of God’s character of being “slow to chide, and swift to bless” echoes the Introit for today’s service, a text taken from Psalm 86, which acknowledges that the Lord is “good and gracious, and of great mercy unto all them that call upon [Him].”

Our Hymnal contains dozens of hymns which credit John Mason Neale (1818-1866) as translator, usually of Medieval hymns originally in Latin or Greek. Neale’s work of eloquent translation had an unrivaled influence in recovering for modern worship the rich liturgical resources buried in the hymnody of the pre-modern Church, both East and West. An active figure in the Oxford Movement, Neale also wrote a number of prose works in addition to quite a few original hymns.

The Sermon hymn today, “O very God of very God,” was first published in 1849 in a collection of hymns for children. Each stanza refers to Christ by way of the imagery of Light, so it is not surprising that this hymn was originally designated as especially suitable for use in Advent, a season in which the dawning of a new Light is celebrated. The hymn was actually linked with the singing of the antiphon traditionally sung on December 21st: “O Morning Star, splendour of light eternal and sun of righteousness: Come and enlighten those who dwell in darkness and the shadow of death.” We’re not yet in Advent, but such declarations are appropriate for singing (and wonder) all year around.

The Offertory anthem today is by Adrian Batten (c.1591–c.1637), an English organist and composer during the period between the Reformation and the English Civil War. This was a time when certain distinctive features of English church music began to take shape. Batten was apparently quite prolific as a composer, but many of his works were lost (destroyed by Puritans?) and most of what survived has never been published and exists only in manuscript form in various libraries and cathedral archives. Our anthem — Haste thee, O God, to deliver me — is based on verses from Psalm 70:

Haste Thee, O God to deliver me, make haste to help me.

Let them be ashamed and confounded that seek after my soul.

Let them for their reward be soon brought to shame, that cry over me: “There, there.”

But let all those who seek thee be joyful and glad in thee,

and let all such as delight in thy salvation say always:

“The Lord be praised!” Amen.

Note that the enemies of the faithful are described in this translation (from verse 3 of the Psalm) as taunting the Psalmist by saying “There, there.” Today, “There, there” might be uttered by a mother to comfort a frightened child, but not by scornful cynics as a mocking jibe. Newer translations render the Hebrew here as “Aha, Aha!”

During Communion, the choir sings a setting of Thomas Aquinas’s great Eucharistic prayer, Pange lingua, by Anton Bruckner (1824-1896). This piece, composed in 1868, is the first of 40 motets composed by Bruckner. Bruckner’s motets are an evident expression of his deep piety; they are discussed in “A Mysterious Sense of Rightness.”

The first of our Communion hymns is “Draw nigh and take the Body of the Lord.” Translated by John Mason Neale (see above), it is from a 7th-century Irish liturgical manuscript, the Bangor Antiphoner. There is a legend associated with this hymn. It is said that St. Patrick and his nephew, St. Sechnall, had quarreled. When they met in a graveyard to be reconciled, angels were heard to sing this hymn. Obeying the command in the opening lines of the hymn, the two entered the church to receive the Eucharist. “Wherefore,” concludes the legend, “from that time forth, this hymn is sung in Ireland when they go to Christ’s body.”

Our Hymnal offers two tunes to which we can sing this hymn; it also works very well with the tune SONG 46 (hymn #69); someday I’ll produce an insert to enable us to use that tune more easily. Meanwhile, we sing it to the tune GARDEN, which was adapted from an English folk song by Martin Shaw (1875-1958), a leader in the recovery of simple yet strong tunes in Anglican hymnody.

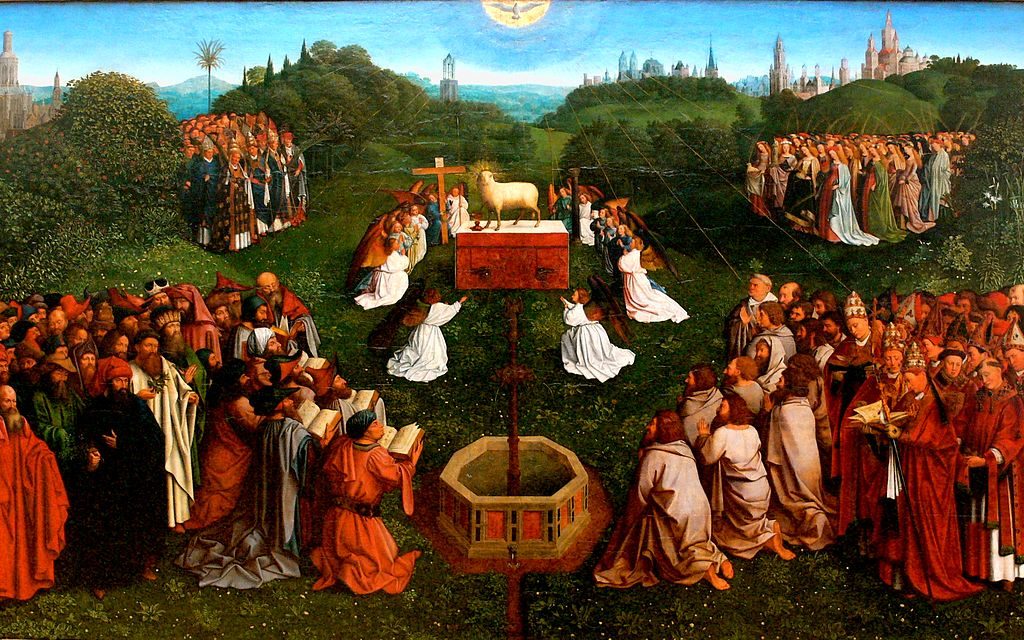

The text to our second Communion hymn is based on a famous painting by Hubert and Jan Van Eyck, “Adoration of the Mystic Lamb,” commonly known as the Ghent Altarpiece.

Painted in the early 15th century, this majestic work graces the sanctuary of Saint Bavo Cathedral in Ghent. The hymn “The Church of God a Kingdom is” was written by Lionel B. C. Muirhead (1845-1925) in 1898 for publication in a hymnal. Muirhead was a friend of the English poet laureate Robert Bridges, who dedicated one of his collection of poems to him. The tune ST. BAVON was composed by organist Charles Edward Horsley (1822-1876), and was named after the patron saint of Ghent.

Our closing hymn continues the theme of the Church as a Kingdom. “I love thy kingdom, Lord” was written by Timothy Dwight (1752-1817), grandson of Jonathan Edwards and the eighth president of Yale College. The tune ST. THOMAS (WILLIAMS) was composed by Aaron Williams (1731-1776), an English music teacher and editor of many collections of church music. His surname in the tune’s name is to distinguish it from another tune called ST. THOMAS.