by Ken Myers

[This article originally appeared in the November/December 2017 issue of Touchstone magazine.]

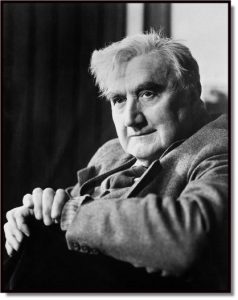

No composer in the twentieth century had a greater influence on the English-speaking church’s musical life — and on the presence of sacred texts in concert halls — than did Ralph Vaughan Williams. Born in 1872 to an English rector and the great-granddaughter of the potter Josiah Wedgwood, young Ralph (rhymes with “safe”) studied piano and violin as a boy. At 18, he enrolled in the Royal College of Music before going on to Trinity College, Cambridge. In both settings he was tutored in composition by some of the giants of English Church music in the Victorian era, including Hubert Parry, Charles Wood, and Charles Villiers Stanford. His classmates included his life-long friend Gustav Holst (best known today for The Planets) and conductor Leopold Stokowski.

Vaughan Williams was not a child prodigy. By the time of his thirtieth birthday, he showed little evidence of outstanding compositional ability. But in 1904, his involvement in two musical projects ignited his imagination and changed the course of his career. That was the year he joined the Folk-Song Society, an organization founded in 1898 to recover native melodies in danger of being eclipsed by the influence (especially among music educators) of the strong German musical heritage. Along with the Society’s early members Sabine Baring-Gould, Cecil Sharp, and others, Vaughan Williams combed the British countryside for tunes and texts that were lodged in the memories of farmers and laborers, critically comparing variants and setting down lyrics and melodies for posterity.

All the tunes of worth

This was no merely academic enterprise; its fruitfulness became evident in the other project that occupied much of Vaughan William’s time between 1904 and 1906. The same year he began tramping around the rural counties in search of rustic ballads, he was invited by a committee of clergy and laymen led by the Rev. Percy Dearmer to serve as music editor for The English Hymnal, eventually published in 1906. “I determined to do the work thoroughly,” he later wrote about the Hymnal, “and that, besides being a compendium of all the tunes of worth which were already in use, the book should, in addition, be a thesaurus of all the finest hymn tunes in the world.”

If the mission of the Folk-Music Society was nationally focused, the English Hymnal was anything but provincial in its content. As hymnologist Erik Routley wrote, the Hymnal enlarged the vocabulary of worship

by reintroducing to currency much that had been lost — tunes from the Genevan psalters of 1542-62, tunes adapted from English folksongs, tunes from 17th-18th century Catholic revival in France, tunes from the Puritan psalters in their original forms and rhythms, tunes by Tallis, Gibbons, and Lawes, and tunes already familiar in corrupt versions often restored to their original versions: this not to mention Bach arrangements of German chorales.

But the aim of the editors was far from “inclusiveness.” In fact Vaughan Williams was adamant about the necessity of excluding certain hymn tunes that he believed were “positively harmful to those who sing and hear them.” For Vaughan Williams, participating in and promoting bad music was not merely an aesthetic offense; it had moral consequences:

No doubt it requires a certain effort to tune oneself to the moral atmosphere implied by a fine melody; and it is far easier to dwell in the miasma of the languishing and sentimental hymn tunes which so often disfigure our services. Such poverty of heart may not be uncommon, but at least it should not be encouraged by those who direct the services of the Church.

In lieu of those mawkish Victorian melodies, Vaughan Williams revived, rehabilitated, or invented dozens of more reliable tunes. Sixteen melodies by Orlando Gibbons were included, and eight from his fellow Tudor composer Thomas Tallis. Four of Ralph’s own hymn tunes were written for this Hymnal. These included the majestic SINE NOMINE, written to set the text of William Walsham How’s invigorating poem “For all the Saints,” and DOWN AMPNEY which conveyed the mystical invocation in “Come down, O Love divine.” Vaughan Williams also enlisted a number of contemporary English composers to contribute new hymn tunes for the Hymnal. From Gustav Holst he received three melodies, including CRANHAM, to which is still sung Christina Rossetti’s evocative Christmas poem “In the bleak mid-winter.”

In lieu of those mawkish Victorian melodies, Vaughan Williams revived, rehabilitated, or invented dozens of more reliable tunes. Sixteen melodies by Orlando Gibbons were included, and eight from his fellow Tudor composer Thomas Tallis. Four of Ralph’s own hymn tunes were written for this Hymnal. These included the majestic SINE NOMINE, written to set the text of William Walsham How’s invigorating poem “For all the Saints,” and DOWN AMPNEY which conveyed the mystical invocation in “Come down, O Love divine.” Vaughan Williams also enlisted a number of contemporary English composers to contribute new hymn tunes for the Hymnal. From Gustav Holst he received three melodies, including CRANHAM, to which is still sung Christina Rossetti’s evocative Christmas poem “In the bleak mid-winter.”

But the most remarkable feature of The English Hymnal was the inclusion of 35 tunes derived from English folk songs. Horatius Bonar’s “I heard the voice of Jesus say” was set to KINGSFOLD, a melody taken from the old ballad “Dives and Lazarus” (a tune for which Vaughan Williams would later write a haunting set of variations for harp and string orchestra). The tune we know as MONK’S GATE is still used to render “He who would valiant be,” a text adapted from John Bunyan. Vaughan Williams learned this melody from Mrs. Herriet Verrall in the hamlet of Monk’s Gate, Horsham, West Sussex. The tune KING’S LYNN, discovered by Vaughan Williams in the venerable ballad “Henry the Poacher,” was employed to accompany the text of G. K. Chesterton’s prophetic prayer “O God of earth and altar.” When Christmas arrives, if you sing “O little town of Bethlehem” to the tune FOREST GREEN, say a prayer of thanks for Ralph Vaughan Williams, who repurposed the fine melody of “The Ploughboy’s Dream” to serve a more placid and edifying text.

A better education

The invitation to serve as music editor of The English Hymnal was accepted somewhat hesitantly. As he later wrote,

this meant two years with no ‘original’ work except a few hymn tunes. I wondered then if I was wasting my time. But I know now that two years of close association with some of the best (as well as some of the worst) tunes in the world was a better musical education than any amount of sonatas and fugues.

The effects of that education are present in much of the music Vaughan Williams went on to write, especially in his understanding of the capacities of melodies. Not long after The English Hymnal was completed, his Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis was premiered; it has become one of his most celebrated orchestral works, and is based on a hymn tune that he included in the English Hymnal. His subsequent sacred choral works — including the haunting Mass in G minor, his under-appreciated Christmas cantata Hodie (with texts from George Herbert, John Milton, and Thomas Hardy), and the magnificent Sancta Civitas, which conveys the awe and glory of St. John’s apocalyptic vision — bear evidence of the fruitfulness of his time thinking about how hymns work.

Vaughan Williams was typically evasive about his own religious beliefs, presenting himself as a “Christian agnostic.” While his own convictions may remain a mystery, his workmanship on behalf of the liturgical needs of the Church continues to be an occasion for wonder and gratitude.