The choral ensemble The Sixteen has recorded a number of albums of Christmas music. They include music from Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque composers, as well as venerable arrangements of well-known carols. In 2006, they issued A Traditional Christmas Carol Collection, followed in 2010 by A Traditional Christmas Carol Collection, Volume II. Under the wise leadership of conductor Harry Christophers, all of these recordings demonstrate discipline and taste shaped by decades of performance of less familiar and more demanding repertoire.

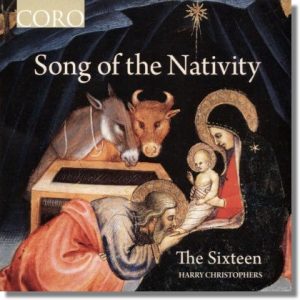

In 2016, The Sixteen issued an album called Song of the Nativity which included seven traditional carols as arranged in the 1928 first edition of the Oxford Book of Carols (which for some of us is almost as dear as another book from 1928). But the bulk of the arrangements were written in my own lifetime and will be new to many listeners.

Listening to this recent collection, I was reminded of how new aesthetic expressions are richly intelligible only in relation to a tradition. What gives the splendid newer works on this recording their power (e.g., Morton Lauridsen’s O magnum mysterium, James MacMillan’s O radiant dawn, and other less celebrated pieces) is their relationship with a history of composition and singing, a matrix of meaning that includes the events celebrated (the Nativity, the shepherds, etc.), the collection of artifacts that memorialize those events (texts, tunes, and arrangements), and the communal practices in and over time that connect us with the transcendent realities embedded in those events, artifacts, and experiences.

In his book The Meaning of Tradition, Yves Congar writes:

If tradition is a continuity that goes beyond conservatism, it is also a movement and a progress that goes beyond mere continuity, but only on condition that, going beyond conservation for its own sake, it includes and preserves the positive values gained, to allow a progress that is not simply a repetition of the past. Tradition is memory, and memory enriches experience. If we remembered nothing it would be impossible to advance; the same would be true if we were bound to a slavish imitation of the past. True tradition is not servility but fidelity.

And later, he summarizes his book’s argument: “Tradition is not merely memory; it is actual presence and experience. It is not purely conservative, but, in a certain way, creative.”

The music on this album is the creative result of a tradition of thoughtfully composed choral music, sustained over time (personally and institutionally) through disciplined singing and active, attentive listening. The word “traditional” is not in this album’s title, but this music would not have been composed or performed as it has been apart from a living tradition of choral music, which is one of the Church’s great gifts to the world.

G. K. Chesterton’s celebration of tradition is well-known. Chesterton declared that democracy means giving our ancestors a vote; it is “democracy of the dead. ” He went on to say: “Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.” It’s fitting that two of the newest compositions on Song of the Nativity are settings of a poem Chesterton wrote in the 1890s, The Christ-child.

The Christ-child lay on Mary’s lap,

His hair was like a light.

(O weary, weary were the world,

But here is all aright.)

The Christ-child lay on Mary’s breast,

His hair was like a star.

(O stern and cunning are the kings,

But here the true hearts are.)

The Christ-child lay on Mary’s heart,

His hair was like a fire.

(O weary, weary is the world,

But here the world’s desire.)

The Christ-child stood at Mary’s knee,

His hair was like a crown.

And all the flowers looked up at Him,

And all the stars looked down.

The first setting of Chesterton’s poem on this album is by Gabriel Jackson (b. 1962); it was commissioned by King’s College, Cambridge, for the 2009 Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols.

The second setting — somewhat more subdued — is a 2007 composition by Alan Bullard (b. 1947) entitled And all the stars looked down.

One more recently commissioned work on Song of the Nativity is Now may we singen, a carol based on a fifteenth-century text and composed by Cecilia McDowall (b. 1951).

These three tracks are among the more recent and less well-known Christmas music on Song of the Nativity. One of the best-known recent works included is Morten Lauridsen’s 1994 setting of O magnum mysterium. If you’ve never heard it, this performance — with fewer singers than is often the case and perfect intonation — achieves a clarity and purity that is lacking in some other recordings. It is (fittingly, in many ways) a gift.

Happy New Year!