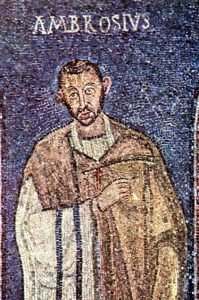

Before being made bishop of Milan in 374, St. Ambrose had been serving in a civic post in northern Italy, having been trained in law. He is best remembered for three achievements that have sustained the life of the Church for centuries: his dynamic preaching against the Arian heresy, his role in the conversion and baptism of St. Augustine of Hippo (354-340), and his belief in the importance of hymn-singing the the life of the Church. He has often been honored as the “father of hymnody,” and for good reason.

Ambrose saw the experience of music as an expression of a divine reality. Calvin Stapert writes that for Ambrose, music was “an echo of God’s Word and Spirit: ‘In the people who are the instruments of the operations of God they hear music which echoes from the melodious sound of God’s word, within which the Spirit of God works.’”

In his book, Te Deum: The Church and Music, Paul Westermeyer describes the event in 386 that made St. Ambrose of great interest to hymnologists:

Justina, the mother of the boy emperor Valentinian, tried to impose Arianism on Milan by taking over the basilica for Arian worship. Ambrose and the catholic faithful staged a sit-in at the basilica, surrounded by Justina’s soldiers. Augustine says that while they were there “the singing of hymns and psalms in the manner of the eastern parts [of the church] was established to keep the people from wasting away through the weariness of sorrow.”

Ambrose appreciated how the experience of harmony in music was an analogue of the experience of harmony (love) in relationships. In his commentary on Psalm 1, he wrote:

A psalm joins those with differences, unites those at odds and reconciles those who have been offended, for who will not concede to him with whom one sings to God in one voice? It is after all a great bond of unity for the full number of people to join in one chorus. The strings of the cithara differ, but create one harmony [symphonia].

Not only did Ambrose write poetry to be sung by Christians and vigorously encourage the practice as a spiritual discipline, he also introduced two common features that shaped liturgical music significantly. As Vincent A. Lenti writes,

First, he had various psalms sung antiphonally by dividing the singers into two groups which alternated in the singing. This ancient method of singing, a practice observed among the Jews, is said to have been introduced to Christianity by Ignatius of Antioch. From Antioch it spread to other churches in the Eastern Roman Empire. Ambrose may have witnessed the practice, or at become aware of it, when he was working [in judicial capacity] in Sirmiujm [before his baptism and ordination].

Second, Ambrose introduced the singing of metrical hymns [i.e., hymns, rather than psalms, based on texts that included a formal rhythmic pattern based on a certain number of syllables in each line], another practice observed in the Eastern churches but previously unknown in the West. In fairness it should be mentioned that Hilary of Poitiers [310-368] had previously attempted to introduce hymn singing, and he might be credited with being the first Latin hymnwriter. However, Hilary was unsuccessful in teaching people to sing hymns, and the surviving fragments of Hilary’s hymns suggest that they were poorly composed and not appropriate for congregational singing.

The texts of a number of hymns are attributed St. Ambrose, but only four can confidently be regarded as authentically his handiwork:

Aeterne rerum conditor (Maker of all, eternal King)

Deus creator omnium (Creator of the earth and sky)

Iam surgit hora tertia (Now came the third hour)

Veni redemptor gentium (from which Martin Luther derived the Advent hymn Nun komm der Heiden Heiland, and which we sing as “Savior of the nations, come”)

RECOMMENDED READING

“Saint Ambrose, the Father of Western Hymnody,”

by Vincent A. Lenti, was published

in The Hymn (October 1997).