by Ken Myers

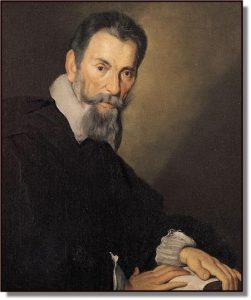

[This article originally appeared in the September/October 2017 issue of Touchstone magazine. 2017 marked the 450th anniversary of the birth of Claudio Monteverdi.]

Douglas Adams, best known as the author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, once offered a brief catalog of the possible range of musical expression. “Mozart tells us what it’s like to be human,” explained Adams. “Beethoven tells us what it’s like to be Beethoven and Bach tells us what it’s like to be the universe.” Like all caricatures, Adams’s summary contains a valuable insight into something that happened in music history, and in Western culture more generally, between the early eighteenth century and the early nineteenth. Bach (who died in 1750) still represented a view of human experience that could be comprehended in the context of a divinely sustained cosmic order. In Beethoven (1770-1827), we hear a personality more in synch with the ideals of the Enlightenment, with its emphasis on freedom and subjectivity. Hence Adams’s contrast (with Mozart somewhere in the middle) between musical expression that portrays all of reality (in a joyous dance) and the later, more modern uttering of the inner uniqueness of the individual. These characterizations are matters of emphasis, not stark black-and-white contrasts, but they are helpful in describing and understanding the genealogy of our own time, in which the self has eclipsed the world almost entirely.

Scholastic versus humanist assumptions

Of all the arts, music has a unique ability to integrate objective order with the subjective response to that order. In music at its best, form and freedom are reconciled. The rationality and intelligibility of the universe can be affirmed musically by means that employ the will and emotions. The actions of body, intellect, and spirit in the giving and receiving of music refute in joyful practice the fragmentation of the human person that modernity promotes. And the eternal purpose of God to unite all things in Christ (Eph. 1:9f.) is actualized in the shared experience of harmony.

But music has also been used in attempts to assert freedom without form and self-expression without submission to the gift of symphonic order in Creation. Music can be abused to simulate primordial darkness and chaos rather than eschatological light and glory. (The fact that many people would balk at the idea of the “abuse” of music shows how modernity’s emphasis on the autonomous self has penetrated our cultural lives.)

Maintaining the balance between affirming the order that precedes us and the experience of subjects who participate in that order — who find their freedom in submission to the order — has always been tricky, in the arts and everywhere else. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, music theory and practice were wrestling with how music might be more affective, might address the feelings more dramatically. In often heated debates that paralleled the Renaissance battle between scholastic and humanistic approaches to intellectual life — approaches that pitted reason vs. rhetoric, proof vs. persuasion, theory vs. empirical observation — musicians and philosophers argued about the propriety of musical structures that violated rules of order in the interest of moving the listeners. These debates were complicated by the sympathy among many of the humanists for (as musicologist Gary Tomlinson characterizes it) “a new human ontology, in which the will assumed a centrality at odds with its scholastic position as mediator between reason and the base passions.” Where the scholastics (in the words of William Bousma) “assumed not only the existence of a universal order but also a substantial capacity in the human mind to grasp this order,” the humanists, Tomlinson argues, held a “fragmented view of reality, and the pessimistic estimation of man’s ability to comprehend it.” These contrasting sets of assumptions presented practitioners of music with a significant challenge, echoed in Douglas Adams’s contrast between a composer who reveals the universe and one who reveals only himself.

Musical codifier of the passions

It was into this contested philosophical, theological, and musical world that composer Claudio Monteverdi was born in Cremona, Lombardy, 450 years ago this year. Having published a collection of madrigals at the age of 19, Monteverdi’s early career was spent at the ducal court of the Gonzagas in Mantua. There he continued to compose mostly non-liturgical vocal music, especially madrigals, which (conductor John Eliot Gardiner judges) “expanded Monteverdi’s finesse in writing for the voice, and pushed his [musical] language to new expressive extremes.” In Gardiner’s view, Monteverdi “is the first codifier of the passions in music, whether it’s love or anger, whether it’s suffering, pathos, languor, religious fervor or erotic desire.”

The latter part of Monteverdi’s career was spent as maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. What Monteverdi learned while composing secular madrigals — whether frivolous, flirtatious, or melancholy — and in his writing of some early operas (his 1607 L’Orfeo is widely regarded as the first great opera) he applied to his setting of sacred texts that display deep human emotions, especially settings from the Psalms. His numerous settings of Psalm 117, Laudate dominum (“Praise the Lord, all nations”) capture both the contagious delight of praise and quiet wonder at God’s faithfulness and steadfast love. He wrote at least three settings of the messianic Psalm 110, Dixit Dominus (“The Lord says to my Lord”), which describes the just and confident rule of a divine King. The text is both gentle and comforting (“the dew of your youth will be yours”) and frightful (“he will shatter chiefs over the wide earth”). Monteverdi’s settings dramatically alternate between quiet solos and duets accompanied by soft strings and full-on choruses with blazing brass. In Monteverdi’s hands, the Psalms are never boring or austere.

Monteverdi characterized the late-sixteenth-century feuds about how to approach music as a choice between the primo prattica (“first” or earlier practice), typical of the well-regulated “cosmic” polyphony of the Renaissance, and the newer secondo prattica, in which musical structure is organized in the interest of conveying the emotions implicit in the text. Monteverdi was certainly a champion of the secondo prattica (which is why he is considered a Baroque rather than Renaissance composer) but he didn’t condemn or even fully abandon the earlier style of composition. His three settings of the Mass, for example, clearly owe a great deal to Palestrina and other Renaissance masters. There are new levels of “subjectivity” in Monteverdi’s style, but not at the expense of acknowledging order. His use of dissonance, for example, could not have the emotional power it does without the backdrop of harmonic givenness.

But you should celebrate Monteverdi’s 450th birthday by listening for yourself. I recommend the 1610 Vespers (performances conducted by Parrott, Christophers, or McCresh are excellent) and the much later collection Selva morale e spirituale (Christophers or Jungianel conducting).